|

Free-market economics is working surprisingly well

Which economic approach works depends a lot on where you start from.

|

One area of seeming bipartisan consensus in America over the past decade is the idea that free-market economics — or “neoliberalism” — has failed, and that our economic system needs to be overhauled. Leftists have always believed this, of course, and in recent years they’ve been joined by more mainstream progressives like the folks at the Hewlett Foundation. On the right, thanks to Trump, tariffs and immigration restriction have overthrown free trade as the reigning orthodoxy. And the GOP in general seems to want to put their thumb on the scale for fossil fuel industries and other traditional sectors.

And in case this wasn’t clear, I have been one of the voices calling for a new economic system! For years I criticized free-market ideology, fretted about the decline of the Rust Belt, expressed suspicion about free trade, and called for industrial policy to revive manufacturing. I wrote many times that the Biden Administration’s industrial policies represented a needed break with the dogmas of the past, and that Trump had enabled that needed shift by destroying the political consensus for free trade. I’m constantly warning that without attention to strategic industries, America and its allies will lose a war to China. There’s a good chance I’ll end up advising the Hewlett Foundation in some capacity on what our next economic ideology ought to be. Despite being elected “Chief Neoliberal Shill” in a humorous online poll back in 2018, I was never an actual neoliberal or a free-markets kind of guy.

So to be clear, when I say that criticism of free markets has been overdone, I’m partly talking to myself. A couple of months ago, horrified by Trump’s tariff policies, I wrote an apology to libertarians, admitting that I had failed to see the political usefulness of their project in terms of maintaining economic sanity on the Right:

But it’s not just the political benefits of free markets that have been undersold; I think the purely economic advantages are also too often ignored.

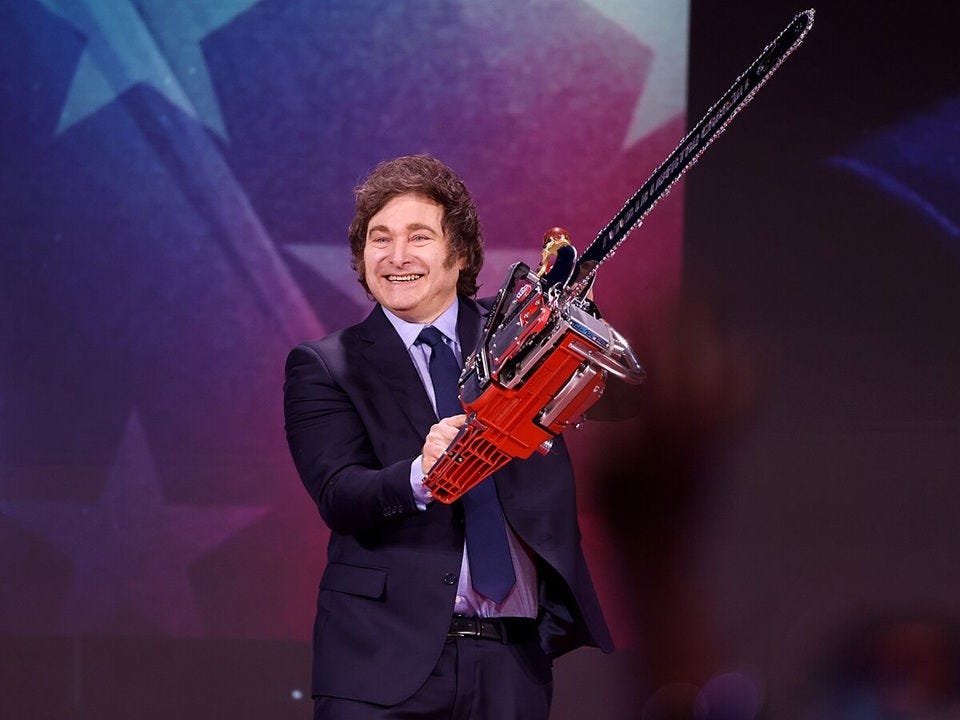

Exhibit A is Javier Milei’s track record in Argentina. A year and a half ago, when Milei was elected President of Argentina, a bunch of left-wing economists warned darkly that his radical free-market program would lead to economic devastation:

The election of the radical rightwing economist Javier Milei as president of Argentina would probably inflict further economic “devastation” and social chaos on the South American country, a group of more than 100 leading economists has warned…[S]ignatories include influential economists such as France’s Thomas Piketty, India’s Jayati Ghosh, the Serbian-American Branko Milanović and Colombia’s former finance minister José Antonio Ocampo…

The letter said Milei’s proposals – while presented as “a radical departure from traditional economic thinking” – were actually “rooted in laissez-faire economics” and “fraught with risks that make them potentially very harmful for the Argentine economy and the Argentine people”…[T]he economists warned that “a major reduction in government spending would increase already high levels of poverty and inequality, and could result in significantly increased social tensions and conflict.”

“Javier Milei’s dollarization and fiscal austerity proposals overlook the complexities of modern economies, ignore lessons from historical crises, and open the door for accentuating already severe inequalities,” they wrote.

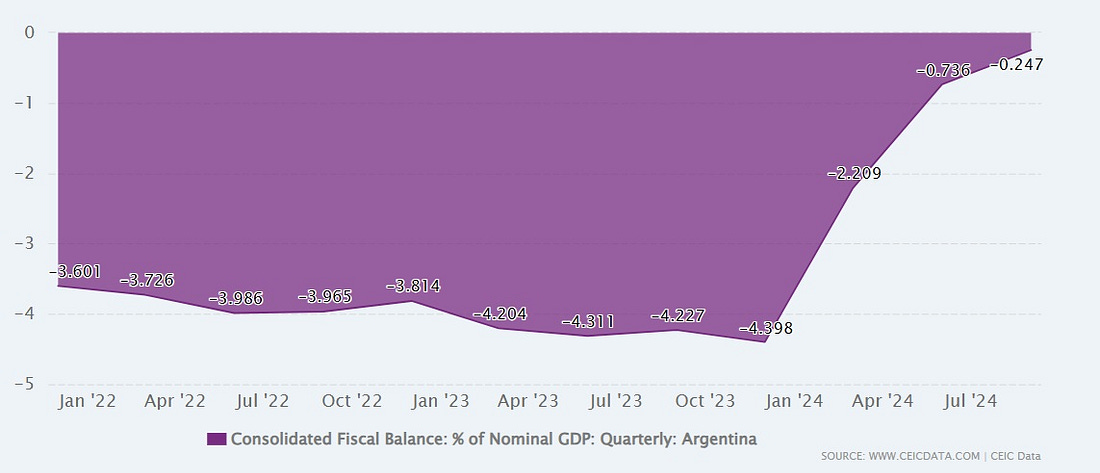

Milei won anyway. His first big policy, and the one the lefty economists fretted about the most, was deep fiscal austerity. Argentina’s long-standing economic model, created by dictator Juan Peron in the 1950s, involved a large and complex array of public works projects and subsidies for various consumer goods like energy and transportation. Milei slashed many of these, as well as cutting pensions, civil service employment, and transfers to provinces. Overall, he cut public spending by about 31%, resulting in a near-total elimination of Argentina’s chronic budget deficit:

|

The point of all this cutting wasn’t just to remove state intervention in the economy — it was to stop inflation. Basically, macroeconomic theory says that if deficits are high and persistent enough, then they convince everyone that the government will eventually inflate its debt away by printing money.¹ And most or all countries that experience hyperinflation end up escaping it only when they get their fiscal house in order. Perpetual deficits were part of Argentina’s “Peronist” system, and it’s probably a good bet that this was responsible for the periodic bouts of hyperinflation that it experiences.

So Milei’s austerity shock therapy was as much about macroeconomics as about micro. So far, it seems to be working. Inflation, which was spiking dangerously before Milei took office and looked like it was headed back into “hyper” territory, has plunged: