|

|

Hi, y’all. Welcome back to The Opposition. I’m going to host a subscriber chat on Substack on Tuesday at 2:00 p.m. EST to answer your questions about the Democratic party and this week’s elections. And then, on our live show later Tuesday evening, I’ll break down the results with the rest of the Bulwark crew. The best way to make sure you don’t miss out? Sign up for Bulwark+ today:

–Lauren

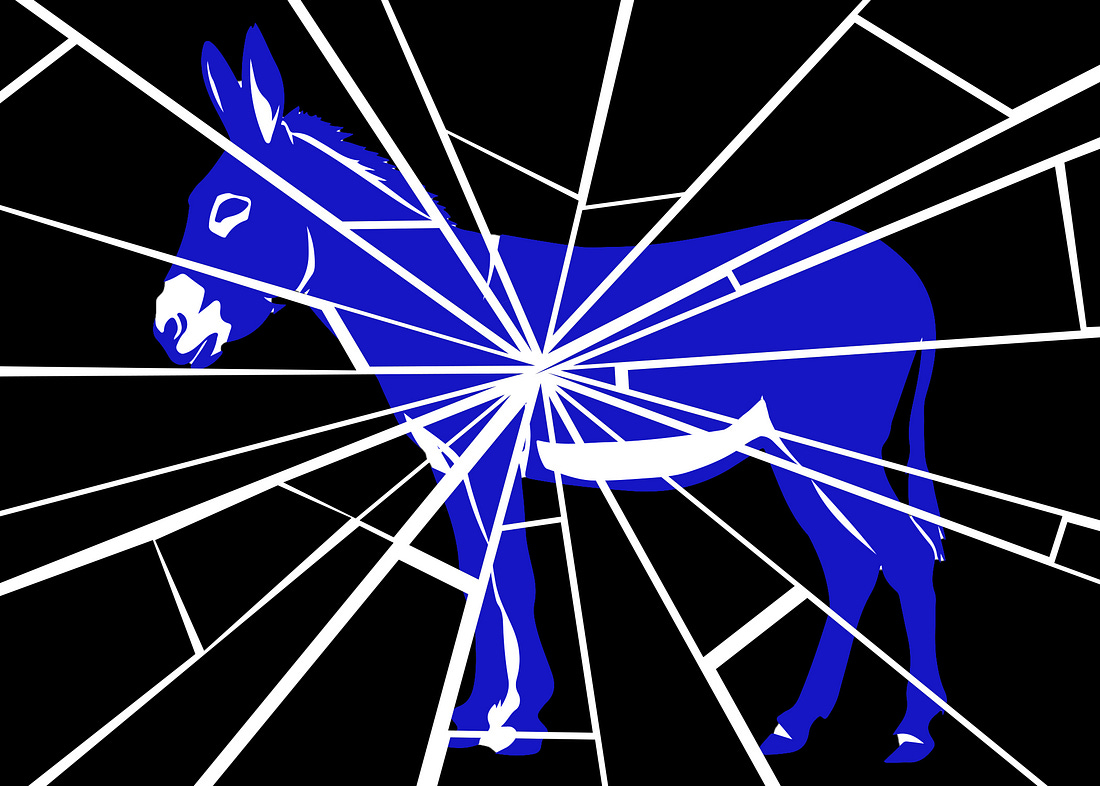

They Dread Trump But Can’t Stop Fighting Each Other: Meet the Democrats

Will this week’s election results bring clarity or just add to the confusion?

THE FIRST OFF-YEAR ELECTIONS of any presidency mark a critical point for the party out of power, if for no reason other than to prove that it can still get its shit together.

That’s especially true for Democrats this year. The party has spent the last nine months desperately trying to galvanize the country around defeating Trumpism. And Tuesday’s elections in New Jersey, Virginia, and New York City will provide the first real test as to whether that’s happening.

But as these elections have neared, the factionalism in the party has grown more intense. Democrats may be united around the proposition that Trumpism is an existential threat to the country, but they are preoccupied with debates over which type of candidate and approach to politics the party should take to combat it.

“The lessons that we take from these off year elections are really important,” said Jenifer Fernandez Ancona, cofounder of Way To Win, a major liberal donor group.

To a degree, recent off-year election cycles have followed similar patterns. During the 2017 cycle, Virginia’s Democratic gubernatorial nominee, Ralph Northam, came under fire from his own Democratic allies for saying he would oppose “sanctuary cities” in Virginia. Democracy for America (DFA), a progressive grassroots group, pulled its support for Northam in protest.

But back then, the Democratic party was still largely convinced that Trump’s election was an anomaly. And Democrats, by and large, were not beset by a feeling of cosmic dread about their future as a party. Hillary Clinton had won the popular vote. And she was seen as a sui generis flawed candidate. DFA was condemned by others in the party for risking a governor’s race. And Northam, in the end, won convincingly.

Today, the pre-spin among Democrats about the candidates on the ballot and the politics they represent feels far more portentous. That might be because the stakes feel higher. But it also has sparked concerns that the party is botching things at a perilous moment.

Progressive strategists argue that Zohran Mamdani’s meteoric rise in the New York City mayoral race is clear evidence that an economic populist message—one monomaniacally focused on cost-of-living issues—is the best way for Democrats to win back power. They attribute his success to his command of the attention economy. And they argue that Mikie Sherrill’s gubernatorial race in New Jersey is closer than it should be precisely because she’s both too milquetoast and has struggled to articulate a vision—beyond just being anti-Donald Trump. Their main conviction is that Democrats win when they inspire excitement among voters, not just when they present a strong resume and draw a weak opponent—as they argue is the case with Abigail Spanberger in the Virginia governor’s race.

“Sherrill destroys the idea of what a safe Democratic candidate is and make[s] clear that someone who is devoid of vision and has solely an anti-Trump agenda will dramatically underperform in 2026 and 2028 if that is our model,” said Adam Green, cofounder of the Progressive Change Campaign Committee. “Spanberger is blessed to have a ridiculous opponent. . . . I think we should be preparing for a real opponent [in 2028] who is well spoken and trying to outflank us on working-people’s issues, not relying on Republicans nominating somebody ridiculous and unelectable.”

Not to shock you, dear reader, but Green’s take is not universally shared among Democrats.

In fact, many party leaders are practically begging their members to stop fawning over Mamdani. They point to polling that shows he is unpopular outside of New York City, that voters outside of major metropolises don’t identify, as he does, as a democratic socialist (let alone a capital-letter Democratic Socialist). Plus, they argue that his current standing in the race isn’t even all that impressive. Polls show Mamdani hovering around 50 percent, well below the 63 percent of the vote that Kamala Harris won in New York City in 2024.

And they’re encouraging others to pause and step back a bit before analyzing Tuesday’s election. A New York City mayoral race is not translatable to many other places in the country. A New Jersey governor’s race is hard to win when your party has held the office for two straight terms.¹

“It is really reminiscent of 2018 when this very charismatic young person wins a very low turnout primary in New York City, goes on to win the general, the whole country loses their collective minds on both the left and the right,” said Matt Bennett, founder of center-left group Third Way, referring to Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s election.

Bennett noted that it was actually a group of Democratic moderates who ultimately flipped enough GOP-held seats that year to deliver the party control of the House. “Is your mission to turn a blue place bluer? Or is it to take power away from Trump?” he asked. “Cause then you better sound a lot more like Abigail Spanberger and Mikie Sherrill than Zohran Mamdani.”

Tuesday’s elections will provide some insights as to which faction is right. But even then, the public arguing is unlikely to end. Democrats on both sides of the debate may be united in believing that Trump’s return to power demands a newfound ruthlessness about how to win, but they are divided over what that will require. And now that these arguments are increasingly happening in public—via a