|

|

Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.

I hoped—prayed, even—I would never have to write about research on ego depletion again. But then a new paper comes along that forces me to take notice. And now I feel obliged to say something.

I won’t go through the whole sordid story; not only is it a long one, but I’ve recounted it a few times already in different venues, including right here in this Substack. So, here is the Cliff’s Notes version.

Ego depletion was social psychology’s golden child for nearly two decades. People went gaga over the idea that self-control runs on a limited resource that depletes with use. Resist that cookie now, fail at the gym later. Simple and intuitive, but ultimately unsupported by strong evidence. The cracks in the resource model of self-control, as it came to be known, appeared in the early 2010s. First came theoretical problems (what exactly was this so-called resource?), then came replication failures. The death blow arrived with not one but two massive, registered replication reports involving thousands of participants across dozens of labs around the world. Result? No effect. Nada. Ego depletion has become the textbook example—literally, it’s in Charlotte Pennington’s undergraduate textbook—of how the replication crisis exposed flawed science.

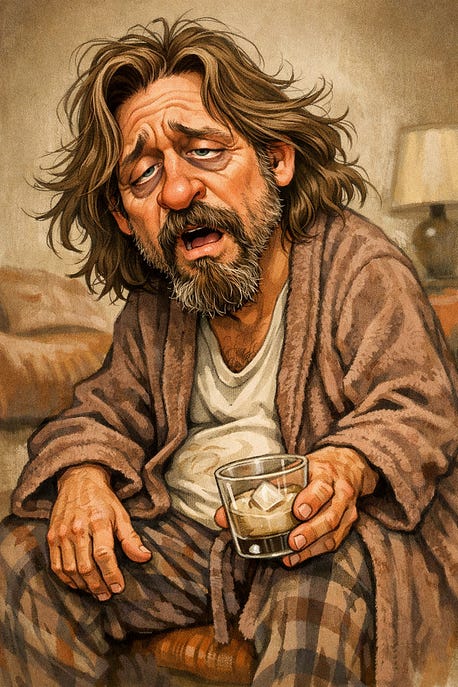

The science says ego depletion isn’t real. Two massive replication studies with thousands of participants found nothing. Bias-corrected meta-analyses found nothing. My own lab found nothing. But tell that to anyone who’s ever lived through a Monday. After hours of grinding through work, resisting every distraction and temptation, managing emotions and impulses, people feel spent. They feel—yes—depleted. They can’t face the gym. They pour themselves another White Russian. They doom-scroll instead of being productive. This experience is near-universal and undeniable.

So, here’s the puzzle: If depletion’s impact on self-control is so obvious in daily life, why have the best controlled lab studies failed to capture it?

The main culprit, I think, is that some of the originators of the theory wanted to carve depletion out as something special, something altogether different from fatigue. I mean there is even a paper with the title, “Ego depletion is not just fatigue”. According to this view, fatigue is a general physical state of weariness stemming from prolonged effort that affects everything you do. Ego depletion, in contrast, was conceptualized as the selective exhaustion of a specific psychological resource dedicated to self-control and executive function. Further, this self-control resource could be depleted by brief acts of self-control—like resisting the desire to eat a cookie or making a difficult choice—that might last only a few minutes.

Once you frame depletion as fundamentally different from fatigue, you get to ignore the entire fatigue literature that goes back over a century. And that literature? It would have told researchers some inconvenient truths. First, fatigue effects typically emerge after hours of effort, not minutes. Second, dominant theories of fatigue are motivational in nature, not resource-based, meaning that when people are tired they become less willing to exert effort, not unable to.

It's not hard to understand why researchers overlooked the fatigue literature. When you're convinced you've discovered something fundamentally new, it's easy to miss how it connects to older work. And academic culture doesn't exactly discourage this. As Walter Mischel noted, theories suffer from he toothbrush problem: everyone wants their own because nobody wants to use someone else's. Novel theories generate grants, attention, and tenure. Building incrementally on existing work? Not so much.

This desire to go it alone came at a steep cost for proponents of the resource model. If they had consulted the fatigue literature—even while maintaining depletion was unique—they might have designed better experiments. They might have realized that a few minutes of resisting the urge to eat cookies wasn’t going to cut it.

So, here’s where we landed: paradigms using brief and weak depletion manipulations failed to consistently produce results. Meanwhile, research on fatigue—evoked by hours of cognitive and physical effort—shows reliable downstream consequences. Physicians prescribe more unnecessary antibiotics at the end of a long day than at the beginning. Medical workers are less likely to sanitize their hands at the end of a 12-hour shift than at the beginning. These effects are real, measurable, and consistent.

Cue this new paper trying to save ego depletion, which evoked depletion with an induction that looks more like how fatigue is evoked in the lab. And—surprise!—it successfully produced a robust effect.

This paper, led by Junhua Dang, is another pre-registered multi-lab study[1]. It involved 14 labs across the world testing 2,078 participants both in controlled laboratory settings and online. Instead of the typical 5–10 minutes of manipulation, participants underwent 30–40 minutes of an intensely demanding cognitive control task before completing a subsequent measure of control.

And the results? Strong, consistent effects that were moderate in size, with virtually no variability across labs. This is about as convincing as results get in psychology.

What strikes me about this approach to lengthening the duration of the initial effort is that we’re watching ego depletion and fatigue converge into the same phenomenon. When you need that much sustained effort to produce an effect, we’re no longer talking about the quick-depleting self-control resource the theory originally proposed. Instead, we’re talking about mental exhaustion.

Even Baumeister seems to recognize this convergence now. In his recent defense of ego depletion, he points to work on fatigue, suggesting that longer, more effortful manipulations can have downstream consequences. On this point, Baumeister and I agree. To me, this is looking more and more like a rapprochement between depletion and fatigue. And I’m here for it. This is the right move, and something I’ve been clamoring for since at least 2015.