|

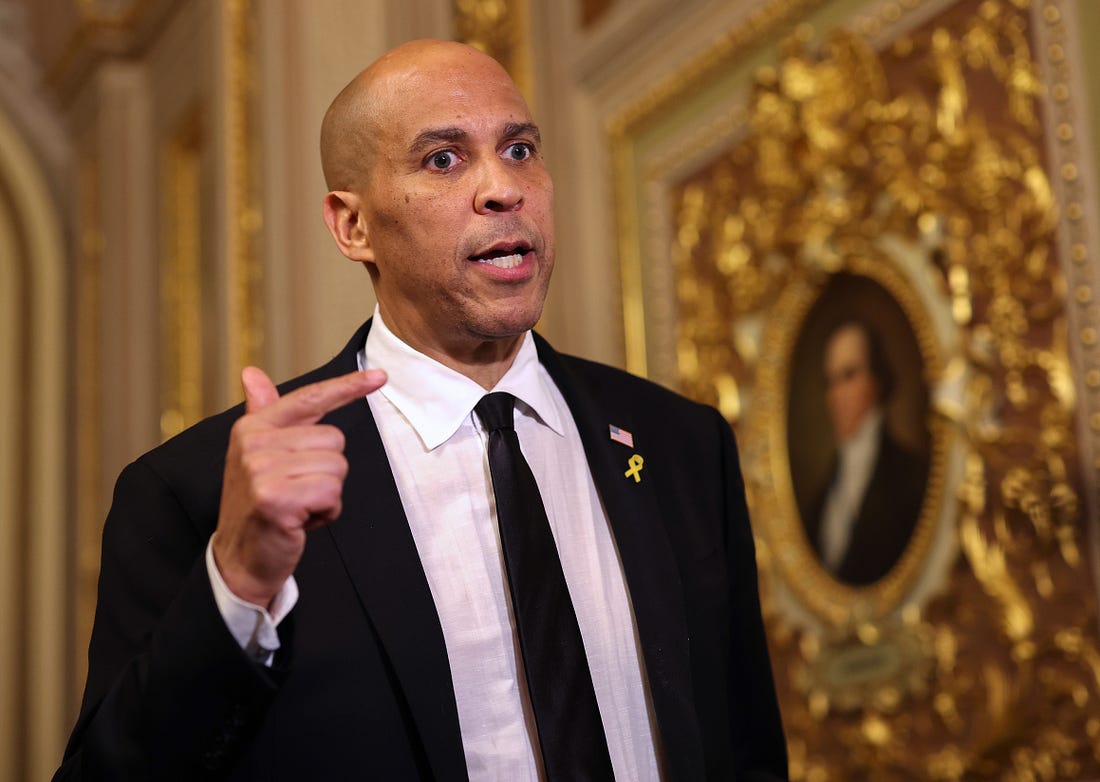

Fam: Cory Booker really got to me and I want to explain why. It’s about hope and it’s about the idea of “good trouble.”

I am a congenital rule-follower. I’ve been worried about things going onto my permanent record since I was in kindergarten. (Not an exaggeration.) So the idea of “good trouble” or “necessary trouble” is foreign to me. But it’s important. It’s something I need to learn about.

Booker used his filibuster not to set a meaningless record, but to grab our attention and let us know that this is a moral moment. That we have to meet it.

I needed to hear that yesterday. Maybe you did, too. If you want to stand with us, we’re here. Let’s get into some good trouble. Together.

Why Cory Booker’s Speech Matters

Booker didn’t “accomplish” anything. He was a voice of one crying in the wilderness. And that’s how you build a dissident movement: with simple acts of witness.

Warning: This is going to be weirdly emotional today. And hopeful. Yes, that makes me uncomfortable, too. But I’m supposed to be honest with you and this is where I’m at.

I’m sure it’ll pass and I’ll be back to normal tomorrow.

1. Cory, Corey, Cori

Let’s start by setting some baselines, before I get carried away.

Cory Booker is not Seneca. He’s not FDR. He’s not a great statesman or a figure of historic consequence. He’s just a guy.

Don’t get me wrong: Booker is, by every account, a good guy. He’s liked by pretty much everyone he’s ever come across. And while he’s a politician, with all of the innate ambition that includes, he’s still the kind of guy you’d enjoy having a beer with, no matter what corner of life you hail from.

Also: Cory Booker’s filibuster didn’t “accomplish” anything. He didn’t stop a piece of legislation from being passed or forge a new political coalition. He didn’t launch a political movement or bring down Donald Trump. The world spins on today precisely as it did before he stood up to talk.

But by God, Cory Booker’s filibuster mattered. Or at least it mattered to me.

Let me explain.

It is painfully easy to get attention these days. Just do a Nazi salute, put it online, and watch what happens. Post selfies while wearing a Camp Auschwitz hoodie. Go into public and claim that immigrants in your community are eating your pets.

You’ll get loads of attention.

The catch is that in order to get attention, you have to be terrible. You have to lie or embrace evil. Civic blasphemy is how I think of it. In the attention economy there is enormous demand for civic blasphemy.

What’s hard is getting attention for messages about truth, or virtue, or love. Not a lot of demand for that stuff.

The problem is: That’s what we need. We need to rally against the nihilism and cruelty of this authoritarian moment. But how do you get attention for that message in a world that is already being ground down? ...

Join The Bulwark to unlock the rest.

Become a paying member of The Bulwark to get access to this post and other subscriber-only content.

A subscription gets you:

| Unlimited access to articles and all our newsletters including Morning Shots by William Kristol and The Triad by JVL. | |

| Ad-free versions of all our podcasts including member-only shows: The Secret Podcast, Just Between Us; and livestreams. | |

| Plus community chats and commenting features. Your support helps keep our work sustainable. Cancel anytime. |