|

|

No “One Last Thing” this issue, because I had a lot I wanted to get into. Below, a case that wasn’t easy to write about. And it won’t be easy to read. But we won’t get through the next four years by just wishing bad things weren’t happening.

–Adrian

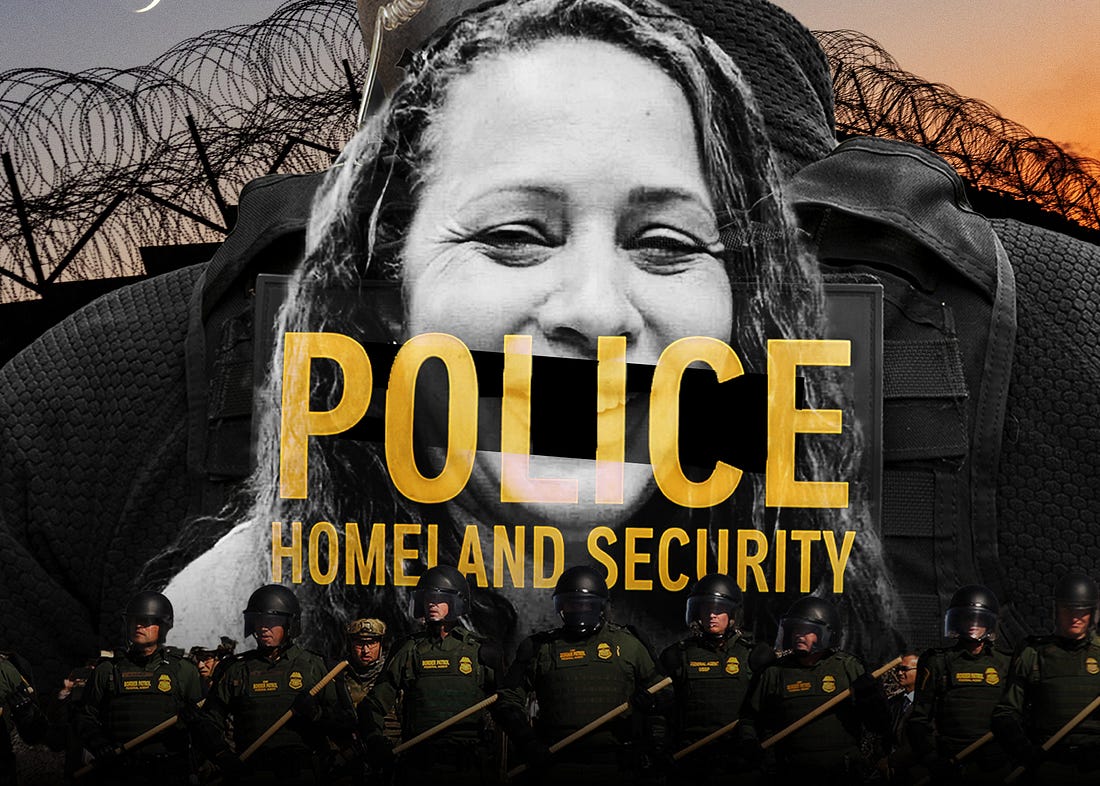

How ICE Tried—and Failed—to Send a Torture Victim to Mexico

An asylum seeker from Colombia had a court order preventing her deportation. Immigration agents didn’t seem to care.

ON MARCH 27, ICE AGENTS LOADED Adriana Quiroz Zapata on a bus, drove her to Mexico, and tried to dump her on the Mexican authorities. The Mexicans, after hearing Zapata’s story of police corruption, threats, torture, and sexual violence spanning years, refused to accept her. They sent her, the ICE agents, and their bus back across the border.

Zapata’s story is just the latest example of a pattern that has emerged early in the Trump administration’s push for mass deportations: Authorities scrambled haphazardly, accountability and oversight were inconsistent at best, and along the way, they likely violated the law, not to mention the rights of a vulnerable, lawful immigrant who’s been through hell.

Zapata is just one of a growing number who have been caught in the dragnet, but her saga illustrates the human costs of what the administration is doing. Now back in detention in El Paso, where she’s been since August 2024, she’s struggling with hyperthyroidism, hyperlipidemia, and prediabetes.

According to her niece, Monica Van Housen, Zapata never missed a Sunday Mass, and she loves her cat, Preciosa, whom she had to leave behind in Colombia. She’s a fan of vallenato music, is a stickler for cleanliness, and enjoys having her nails done and taking care of her hair.

In 2021, Zapata was in a relationship with Steev Manuel Puello Restrepo whose father, Carlos Puello, is a high-ranking lieutenant in the Colombian national police and a member of a wealthy and influential family, according to immigration court documents. When the couple tried to claim asylum in the United States that year, Restrepo passed the test to establish “credible fear” in his home country and was allowed to enter the United States. Zapata did not, her lawyer, Lauren O’Neal, said. So Zapata was sent back to Colombia while Restrepo remained in the United States.

The following year, Restrepo was renting a room at the home of Zapata’s sister in New Jersey. According to a North Bergen Township police report shared with The Bulwark by a member of Zapata’s family, Restrepo physically attacked Zapata’s sister. Zapata’s niece, who was a witness, reported that he struck her mother so hard that her breast immediately began to bruise. Restrepo denied that he had assaulted Zapata’s sister and called Zapata in Colombia while in the presence of a police officer, presumably so that she would defend him. She instead informed the officer that Restrepo had told her about attacking her sister. Officers placed him under arrest. “This incident,” immigration court records explain, “ultimately led to [Restrepo’s] deportation.” Restrepo told Zapata in a phone call after his arrest that he blamed her and her sister for his deportation, according to immigration court records.

Upon returning to Colombia, Restrepo, backed by what immigration court documents called his father’s “substantial influence on the national police force,” began scheming for revenge against Zapata: “On at least ten different occasions from 2022 to 2024, [Restrepo] and uniformed police officers came to [Zapata’s] home, destroyed her things, threatened her, severely beat her, and raped her.” She tried to report the first attack to police, but they refused to take her report after they heard Restrepo’s name, according to those same documents.

Zapata moved twice within Colombia during that period, including to a location four hours from her home in Medellin. But even though she kept each address private, Zapata found her each time, the immigration judge found in his ruling.

She finally fled for her safety to the United States last August. But fleeing trouble, she soon found more—this time at the hands of U.S. authorities.

ZAPATA WAS IMMEDIATELY DETAINED in El Paso. On December 10, 2024 while still in detention, she signed an untranslated document waiving her right to parole release despite her pending case, according to O’Neal. But she later alleged that agents had coerced her to do so. She and her lawyer subsequently filed a complaint with the Office of the Immigration Detention Ombudsman (OIDO). It was successful, leading to a deportation officer being reassigned; that agent no longer has any interaction with detainees, O’Neal said.

In addition to the OIDO complaint, O’Neal also contacted the office of Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Texas), who represents El Paso, to help her client’s case. According to O’Neal, after the complaint to OIDO and the outreach to Rep. Escobar, ICE agents in El Paso became more vindictive toward Zapata.

Before the ICE agent was reassigned, he approached her in detention and told her he had ways of keeping her languishing in El Paso for an extra eight to nine months, O’Neal told The Bulwark. After receiving those threats, Zapata filed another OIDO complaint on January 8, which went nowhere.

(The Trump administration gutted OIDO and other offices that were part of civil rights and immigration liaison services on March 21, explaining that “they often function as internal adversaries that slow down operations.”)

ICE El Paso officials did not reply to a request from The Bulwark for comment. A DHS spokesperson responded by asking for a copy of the immigration court ruling documents—but after being provided them did not respond further.

Zapata’s case finally came up for adjudication in February of this year. During the proceedings, Immigration Judge Stephen Ruhle characterized what Zapata had experienced in Colombia during Restrepo’s series of attacks as “extreme physical and sexual abuse,” noting that she had broken teeth and stab wounds, among other injuries. He ruled that the Convention Against Torture prevented her from being deported to Colombia.

After Ruhle’s decision, Zapata’s niece contacted the office of Rep. Rob Menendez (D-N.J.), her representative, seeking help with Zapata’s case, according to O’Neal.

About a month later, ICE officials in El Paso told O’Neal that Mexico had agreed to take Zapata, but that she wouldn’t be sent there anytime soon.

Three days later, ICE agents tried to ship her across the border.

According to asylum law, Zapata can be sent to a country that’s not her native home if that country accepts her and if it is a country where she already has ties. But Zapata has no ties to Mexico, and they did not accept her. O’Neal alleges that agents again coerced Zapata to sign an untranslated voluntary removal document entailing her agreement to be barred from the United States for twenty years.

“What she thought was, either she signs the form or they throw her off the bridge, she doesn’t know what else they could do,” Van Housen told me. “She just thought the worst, honestly—that she could die in their hands.”

If not for a little patience by the Mexican immigration authorities, Zapata might have become an undocumented immigrant in Mexico. At the border, as Mexican authorities asked ICE to return her bag with her passport to her, her niece says Zapata prayed to God and invoked her late mother: “Whatever happens, Mom, please help me.” That’s when Mexican officials called Mexican immigration authorities. When ICE returned with Zapata’s belongings, those officials said she was not going to be allowed in.

In a recorded phone call that O’Neal provided to The Bulwark, the Instituto Nacional de Migración, which controls migration into Mexico, confirmed it did not have information in its system on accepting Zapata, in apparent contradiction to what O’Neal said the official in the ICE field office had claimed.

ZAPATA, NOW 53, REMAINS IN A DETENTION CENTER in El Paso. Van Housen said her aunt is nervous, and that she has diarrhea and is vomiting because she doesn’t know what’s going to happen to her. She says Zapata’s toenails are turning black, and one of her teeth is chipped and turning brown.

“To tell you the truth, I have no words to explain how mentally and physically sick she is,” Van Housen said.

O’Neal said she believes ICE was taking an unusually vindictive approach toward Zapata even before Trump came to power, but that his presidency has allowed the agency to drop any pretense of trying to follow the law. “They were going to be retaliatory to Adriana regardless, but Trump coming in made it a lot easier for them,” she said. “They’ve essentially been instructed to see what they can get away with, and they’re retaliating over us trying to keep them accountable. They don’t like to be accountable.”

Trump campaigned on mass deportations, and has reportedly been