| Points of Return will now try to cover everything that’s hit the world economy in the last 24 hours, but not succeed. Sorry about that. The Trump “Liberation Day” tariffs were a big deal, as was the market reaction Thursday, which saw the most brutal selloff since the Covid lockdowns started in March 2020. Here are some of the more important questions and some tentative answers. What Just Happened? As covered yesterday, the reciprocal tariffs the president announced weren’t reciprocal. Some of them seemed ludicrously out of proportion. We now have clarity on how they were arrived at from the US Trade Representative’s office, which explains that they were calculated using this ludicrous Greek equation: Long story short, the Greek letters are assumed to cancel each other out, so this equation is a fancy way of dividing a country’s net exports to the US (the stuff it exported minus the stuff it imported) by its exports to the US. The higher this ratio, the more protectionist the country must be. This is absurd on many levels, as pointed out by Nobel Prize-winning trade economist Paul Krugman and by colleague Matt Levine. Here’s my own attempt to explain this in a video: The new tariff regime is not reciprocal to anything, but instead is retaliatory in proportion to how big a surplus in goods trade a country happens to have with the US. This chart from Exante Research illustrates it beautifully: Investors had hoped for genuinely reciprocal tariffs. Until Liberation Day, reciprocity in trade measures referred to matching other countries’ tariffs product by product; if you tax my vans at 15% and my light vehicles at 10%, then I will charge the exact same rates on your vans and light vehicles. This has the disadvantage of being really difficult to work out (it’s why trade negotiations take a long time), but it’s visibly fair, and — critically in the current environment — it wouldn’t have involved raising US tariffs by much, because the free trade agreements already in place tend to ensure that levies are broadly reciprocal. Reciprocal tariffs under the Trump 2.0 definition don’t reciprocate for anything. Rather, they retaliate against countries for selling more to the US than they buy from it, treating the entire global economy as a zero-sum game. What Are We Scared Of? The greatest issue concerns the dollar. Relative to the rest of the world, US assets have boomed ever since the Global Financial Crisis and went into overdrive after the pandemic stimulus programs in 2020. At that point, America let the liquidity flow, and attracted massive flows from other countries into its stock market. Following Julian Brigden of MI2 Partners, you could call this “vendor financing.” The growth in European holdings of US stocks has been breathtaking: This has been helped by a virtuous circle. The flows push up the dollar, which increases the returns for foreign investors and fosters confidence that the US is unstoppable, thus drawing in more funds. It’s a classic example of what the hedge fund manager George Soros, mentor of US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, calls reflexivity, or the ability of the market to create its own reality. The problem arises when something obtrudes. In terms of Swedish krona, for one example, the S&P 500 delivered returns of 140% in five years, but is now in a bear market, having dropped 20% since the turn of the year: The profits European investors are still sitting on are considerable, and they’ll now have an incentive to take those profits, which could be needed for investing in a much more difficult trade war environment at home. US stocks, particularly Big Tech, have been a kind of piggy bank for the world. The risk now is that foreign investors will smash the piggy bank. For an idea of what’s at stake, look at Apple Inc., which stands to be grievously hurt by the new tariff regime. Its market cap almost touched $4 trillion three months ago. Now it’s nearly back to $3 trillion. The value it has lost is greater than the highest market cap ever accorded to Walmart Inc.: If trade flows are going to fall, as is more or less inevitable if these tariffs are imposed for any period of time, the risk is that capital flows will have to follow. That’s bad for the US, which attracts masses of capital, but the danger is evident in this chart from London’s Absolute Strategy Research: Capital can move much more quickly than goods can. The risk is that the virtuous circle will turn vicious and upend the US financial system. What Makes This Stop?

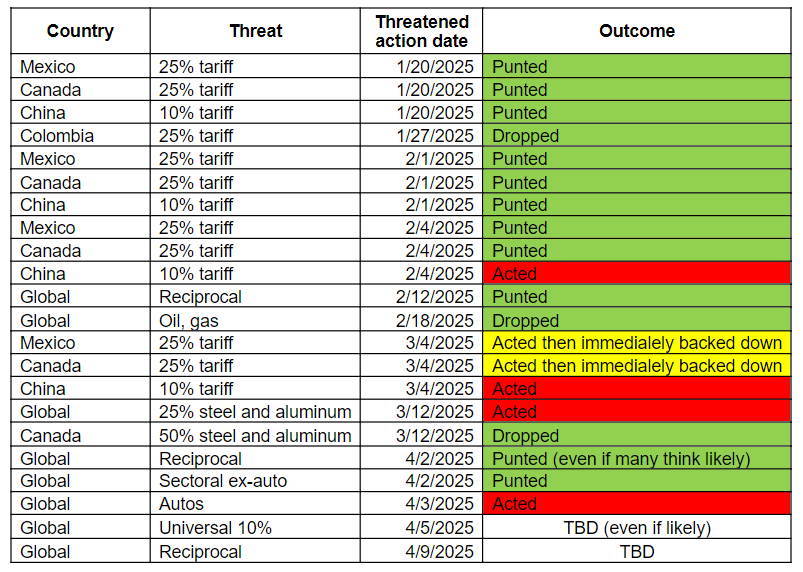

There are a number of guardrails that could reel in the tariffs. The most obvious candidate is the president himself. Andrew Bishop of Signum Global Advisors counts 22 separate tariff announcements from Trump already. Most didn’t happen:  Source: Signum Global Advisors It’s always possible that he could retract again. That said, this announcement was so big and so heavily hyped in advance that retreat grows harder. It will also be difficult to negotiate because other governments will be under pressure at home not to give way to a perceived bully. Mark Carney’s hard line, which looks like it might win him this month’s Canadian election, gives a good foretaste. Why else might we see a retreat? The US services sector could be a problem, as the focus on goods trade obscures the fact that the US enjoys a big surplus in services. If EU companies eschew US firms, Americans have much to lose: Viktor Shvets of Macquarie points out that in 2023, the US exported more than $300 billion in information and communications technology and business services, yielding a net surplus of $120 billion. US royalty and license fees (mostly tech) reached a net surplus of $90 billion, while financial services generated a surplus of $63 billion. “Expanding the scope of the trade war will be inflammatory,” he says, “but it seems the EU (and Canada) might have decided that one can only negotiate with the US from a position of strength, and services are the US’ Achilles heel.” The other guardrails have been perceived to be the stock market, the economy and the political system. So far, the administration has dealt with a bigger selloff than ever happened in Trump 1.0 (before Covid) and scarcely blinked. Inflation could be more impactful. The last election hinged on this very issue, and these tariffs would on the face of it be inflationary. As far as stocks are concerned, there’s also a perverse hope that the weakening economy will force a rethink. Non-farm payrolls for March will be published soon after you receive this. The latest private-sector survey of layoffs produced by Challenger, Gray & Christmas suggests that the administration’s efforts to cut the federal workforce are having an impact: The Fed doesn’t want to cut rates because of the risk of inflation, but a pickup in unemployment might change that. Evidently, many in the market still hope that there will be some kind of a “Fed Put” even if there isn’t a “Trump Put.” The futures market’s estimate of where fed funds will be by the end of this year has suddenly dropped to its lowest in six months: This looks a little like wishful thinking. The best hope for making these tariffs go away is political. If stock market losses and rising inflation have a bad enough impact on the polls, and prod Republicans in Congress either into opposing tariffs or into speeding up efforts to cut taxes and regulations (which would be market-friendly), the situation would get a lot easier. The bottom line remains that it’s hard to see how things can get significantly better without getting much worse first.

How Might This Work? Who Wins? Bessent has been clear that he had three aims from markets — a weaker dollar, cheaper oil, and lower 10-year Treasury yields. In combination, these allow for far greater US dynamism. The problem is that these things seldom overlap with a strong economy, so it was difficult to see how his targets could be achieved without a recession. The idea of a “Mar-A-Lago Accord” to negotiate a weaker dollar has been popular in large part because it would allow the US to square this circle. In the event, with the economy still doing fine, all of those aims are on target. The only problem is that they’ve been accompanied by such a severe fall in the stock market. This is how those measures have moved since Trump was inaugurated: These offer the financial building blocks for the US economy to keep ticking nicely — while Europeans and Asians might have a problem as their own currencies rise against the dollar. What Do You Invest In? This is a rotation as much as a selloff. Defensive stocks are doing very well. Many consumer staples companies rose during the carnage. And at times like this, it’s always appealing to rely on human weakness. There will always be a demand for tobacco, and at times like this it seems very appealing: Beyond that, there’s still plenty of space to invest elsewhere. The danger, of course, is of a self-reinforcing reflexive cycle, but there’s still a lot of juice in moving money out of the US. This is how the US has performed compared to the rest of the world since the beginning of 2020: It always sounds trite to say that there are opportunities in massive negative events, but it’s always true. Unless Trump performs a complete U-turn on his tariffs, however, it would be wise to throw out the playbook of the last five years. Different forces are at work now. |