|

“And our choices were few and the thought never hit/ That the one road we traveled would ever shatter and split” — Bob Dylan

I’m trying my best to find things to write about other than Trump’s tariffs, because I figure you lovely readers don’t just want to hear doom and gloom all the time. So here’s a post that people have been asking me for for quite a while.

There are a lot of things in life that I’m not very good at — foosball, debugging code, remembering people’s birthdays, and so on. It’s a long list. But one thing I am good at is having friends. Not everyone knows this about me, but in fact I’ve always been an extremely social person. I’m pretty good at assembling a cohesive group of friends, who do things together regularly and become friends with each other.¹ And at least since my college days, I’ve also had quite a number of very close friends — people I can tell anything, people I know will have my back, some who feel as close as family.

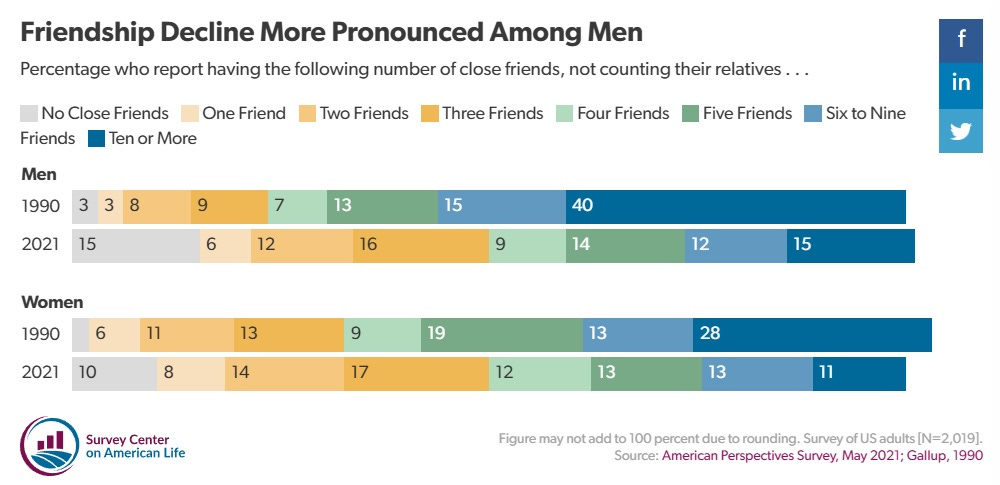

Apparently this is somewhat unusual for an American man in this day and age — or at least, more unusual than it ought to be. In 2023, Pew reported that only 38% of Americans have five or more close friends. An AEI survey in 2021 showed big drops when compared to earlier surveys:

|

And in 2023, the Surgeon General published a report entitled “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation”, exploring various possible factors at work.

The loneliness trend seems to predate the pandemic, and to be especially acute among young people. Derek Thompson had an excellent podcast episode back in 2022 when he interviewed the economist Bryce Ward about this so-called “friendship recession”:

Why America is Suffering a 'Friendship Recession' The Ringer |

Ward’s chronology of the friendship recession sure makes it sound like smartphones and social media are at least one likely culprit:

The American Time Use Survey started in 2003, and between 2003 and 2013, people spent basically the same amount of time with their friends. They spend slightly less than seven hours [per week] with friends. If you expand the definition of friends to include family and neighbors and coworkers outside of work, that whole set of people—including your friends, companions—they spent about 15 hours. And then in 2014, we started slowly kind of ticking down. And by 2021, we have this data, we’re spending less than three hours [per week] with our friends, we’re spending less than 10 hours with our companions, and what are we doing with that time we used to spend with our friends and companions? We’re now spending it alone. We’ve increased the amount of time we spend alone by almost 10 hours.

I don’t have policy ideas for combating this trend, except for the obvious one of banning smartphone use in schools. This obviously won’t work past a certain age, and smartphones are not the only cause of loneliness. I would love to tell you that building denser, less car-centric urban environments would help people have more friends, but unfortunately the evidence shows that people in big cities are just as likely — or even more likely — to be lonely compared to people who live in the suburbs.²

So while we search for policy solutions to our national epidemic of friendlessness, I thought I might offer some personal thoughts on how I’ve managed to have such a good quantity and quality of friends over the years. I realize that my own experiences aren’t universal and that my own techniques won’t work for everyone. Other people have their own approaches — just last year, the blogger Cartoons Hate Her wrote a similar guide, which is longer and more detailed than mine.

But anyway, here’s how I do it.

Why making friends gets harder after age 30

I titled this post “How to have friends past age 30”, because most of the people who ask me for advice about this, or who complain about not being able to make friends, are over 30. I think much of this advice will work for young people too. But there are definitely some reasons why making friends gets harder as you age.³

Most obviously, there are just a lot more demands on your time. A lot of people in their 30s get more serious about their jobs and careers. People also tend to get married and have kids, which takes up a lot of their time. People’s parents start getting old, and they have to do eldercare. There are simply fewer hours in the day for socializing, and you’re more tired during the free hours you do have.

Also, if you’re an educated type, much of your youth is spent in various institutions that throw you together with a bunch of other people your age and of a similar social class — high school, summer programs, college, study abroad, grad school, internships, entry-level cohorts at work, and so on. Meeting people isn’t as hard because there are higher powers doing a lot of the work for you.

But there’s another big reason that friendships get tougher as you age, and it’s that life experiences diverge. A big part of making friends is relating to other people, which requires finding some kind of commonality — some shared life experience or emotion that lets you understand someone else better by making an analogy with yourself. It would be very difficult to make friends with an alien spider, or a robot (though there are many great science fiction novels about people who surmount this challenge).

When we’re young, the people growing up around us are fairly similar to us — they usually go to the same schools, watch the same TV programs, and have broadly done similar things in life. College and other institutions sort us by social class and shepherd us through even more shared life experiences. Yes, there are plenty of differences between young people, but the structure of our society — and of life itself — means that the similarities are almost always there, ready to form the initial basis of a new friendship.

As you get out into the working world, life paths diverge. Maybe one person lived overseas and then got a PhD, while another went to work for a big company and stayed in the town where they went to college. People get married and divorced, some have kids and some don’t. Life-changing health problems, both physical and mental, become more common. Beyond these easily quantifiable factors, there are an infinitude of subtly divergent life experiences that accumulate steadily over time. By their 30s, people are much more alien to each other.

This obstacle isn’t insurmountable, but it helps if you realize it’s there. You need to understand that as you get older, most friendships will be voyages of exploration, where you spend a long time and a lot of effort understanding someone else’s unique life experiences. So be prepared for that, and try to see it as a rewarding exercise — working to understand someone else broadens your own perspective, and makes you a more well-rounded person too.

(Actually, this is probably good advice for young people too. Some young people tend to just assume that their shared experiences of school, or pop culture, or sports make them the same as their friends, and thus ignore some of the deeper differences.)

Anyway, making friends past age 30 usually means you have less time, less energy, less help, and less shared experience. But it’s still very possible.

How to have a friend group and meet lots of people

Individual friendships are great. But most people don’t just want one-on-one interactions — we want a gang of friends who all hang out together. We want something like this:⁴