| In the climactic scene in Trading Places — easily the funniest film about commodity trading ever made — Mortimer Duke realizes he has lost his fortune in the day’s trading, and screams, “Turn those machines back on!”, thinking that if trading could only start again, things would go back to normal. Larry McDonald of Bear Traps Report offers this as a market analogy: Today’s US equity market backdrop reminds us of this delusion. Much of the Wall St. sell-side research community doesn’t realize we have moved to an entirely new regime… The mad mob thinks we can simply ‘turn those machines back on,’ not realizing we are far, far, far away from that lost world.

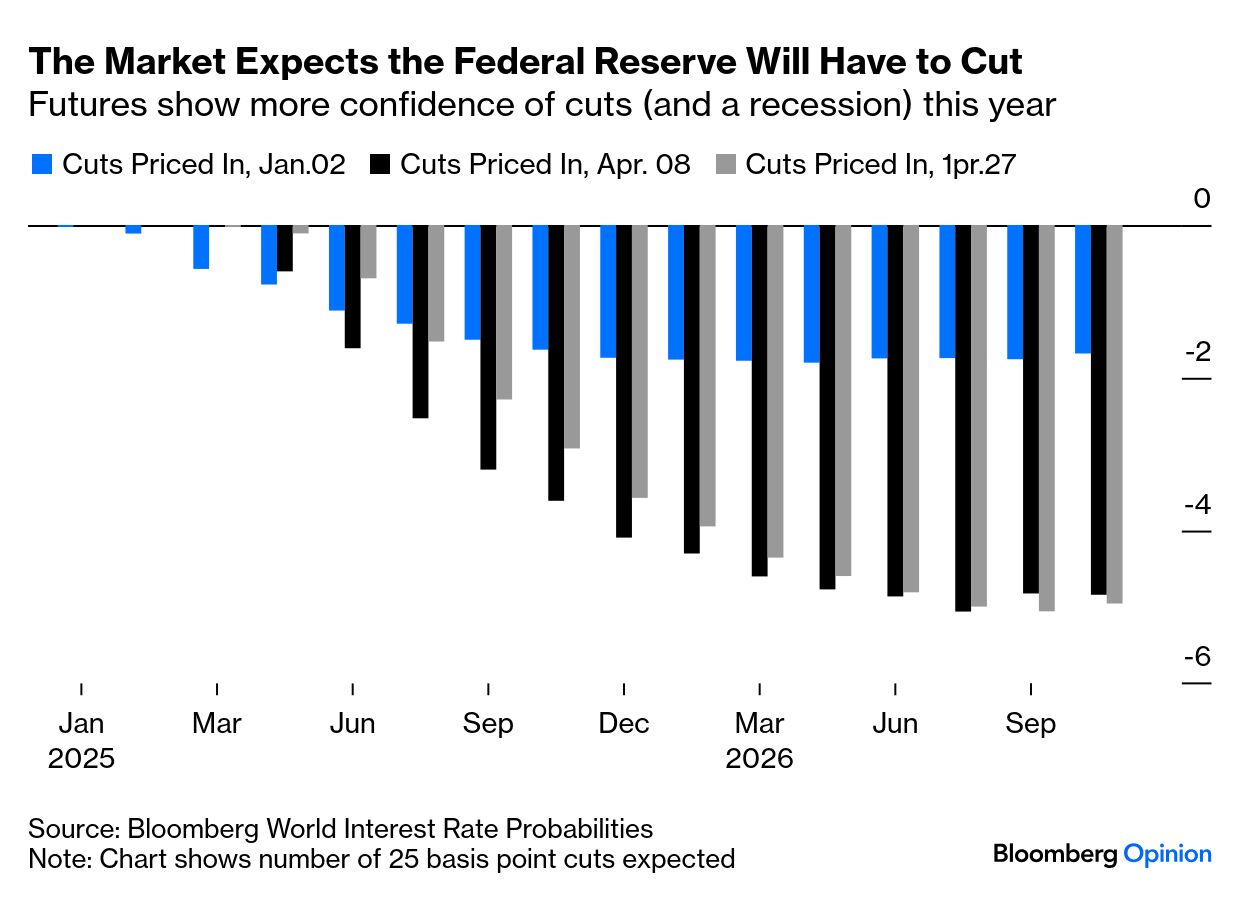

Traders behaved last week as though they could hit the usual on-switch, after the spasm that greeted the Trump 2.0 agenda. The rally was potent, aided by confirmation that Jerome Powell wouldn’t be fired as chair of the Federal Reserve, more emollient noises about tariffs on China, and a generally good start to the earnings season. It even triggered the Zweig Breadth Indicator for only the 18th time in 80 years, an almost foolproof bullish signal for the next 12 months; it only happens when when the share of stocks that are rising moves from less than 40% to more than 61.5% within a 10-day period. In other words, this rally lifted a lot of boats, and left many pointing in a positive direction. The recovery of the VIX index of volatility since the April 9 announcement of a 90-day delay on tariffs has been a sight to behold: The tariff regime still on the books remains considerably worse than what was regarded as the worst-case scenario a month ago, but nobody trading the market on a short-term basis can afford to ignore signals like this. Risk appetite and liquidity suggest that risk assets can continue to move higher for now. That’s true whatever the long-term destination might be. Viewed in only a slightly longer context, the S&P 500 is essentially, as the Duke brothers might have wanted, back where it was a year ago. This is true whether you compare it to bonds (proxied by the TLT exchange-traded fund, which tracks Bloomberg’s index of long treasuries), or to other stock markets (proxied by the MSCI All-World excluding US index). Within the stock market, what had seemed a clear turning point is now murkier. This is how the Magnificent Seven have fared compared to the average stock in the S&P 500 since the turn of the decade: The toppling of the Magnificents seemed obvious a month ago, but now it’s more ambiguous, as they keep returning to their 200-day moving average relative to the average stock. Their upward trend has been corrected for post-election excess, but it’s not been ended. Some changes have lasted, starting with expectations of the Fed. The chart shows the number of rate cuts that had been priced in at the turn of the year, on April 8 — the point of maximum angst before Donald Trump delayed tariffs the next day — and currently. Markets expect the Fed to cut far more aggressively now than they did before Trump took office. That hasn’t changed since the tariff reversal, other than that early emergency cuts seem less likely:  The reason for this: Traders think a recession is far more likely. At present, they expect the Fed to hold off cutting for a while until the inflationary impact of the tariffs is clear, and then slash rates about five times. Such a pattern only makes sense if a slowdown takes hold. Lower rates historically help equity prices, of course, but not when they’re a response to a weak economy. Rightly or wrongly, most investors are working on the assumption that even if tariffs come down significantly, they will still be too heavy to avoid a recession. Meanwhile, the dollar’s decline hasn’t been arrested. In some ways, this is still not that big a deal. On a broad trade-weighted basis, it remains higher than for much of this decade, and its decline isn’t as strong as the fall after the Covid panic of 2020, nor after US inflation peaked in 2022: But this ignores the fact that both those declines came as risk appetite returned after fear had driven money into the dollar as a haven. This is different. Fear is rising, and the dollar is still selling off. That implies broken confidence in the US, which has been a dominant narrative for weeks. The idea of American exceptionalism built up in markets over decades, and had grown extreme in the five years since the pandemic. That cannot be priced out in a few weeks, and markets won’t move in a straight line as funds leave the US. Julian Brigden of MI2 Partners argues: The disruption caused by the Trump administration’s assault on geo-political and economic norms would/will have started a new, secular ball rolling where faith in American exceptionalism will be broken beyond repair. BUT, that doesn't mean we shouldn’t be flexible enough to take profits and reset positions into the inevitable counter-trend correction when we reach climactic narrative adoption.

Last week saw a potent “counter-trend correction” as people took an exciting narrative too far and too fast. Whether it comes true depends on where policy moves from now, and the reactions to it. If almost all the announced tariffs are repealed and China and the US thrash out an accommodation, while Washington resumes enthusiastic support for Ukraine and works closely with European allies, then things will begin to look very different. The mood music of the last few days suggests that all of this is just about conceivable. Tax cuts on top — which Trump is sensibly returning to the conversation — would juice things up further.  Dan Aykroyd about to disrupt the commodities machine.

Source: ‘Trading Places,’ 1983/Paramount/Archive Photos/Getty Judge for yourselves how plausible that scenario is. Trump doesn’t admit errors, so it will be hard to achieve. Meanwhile, the overwhelming sentiment, particularly outside the US but also on Wall Street, is that a Rubicon has been crossed, and trust in the US irretrievably damaged. Arguably, even the the scenario I just mapped out wouldn’t restore it. Evidently, many still believe the machines can be switched back on. They shouldn’t be ignored, and trading never goes in a straight line — but it would make sense to take last week’s bounce as an opportunity to continue positioning for the gradual decline of American exceptionalism. |