|

|

Friday afternoon, the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 In one of the many immigration cases currently in the courts as a result of Trump’s deportation of alleged Tren de Aragua gang members without any due process. In A.A.R.P. v. Trump, the Court enjoined the government from summarily deporting alleged gang members under the Alien Enemies Act while litigation over the constitutionality of those deportations works its way through the courts.

The decision is a per curiam opinion, which means no single justice signed it, but it represents the view of seven of them. You can read the full decision here. It runs to 24 pages, and is worth spending some time with, if only to get the Court’s tone. Suffice it to say, the majority is displeased with the government.

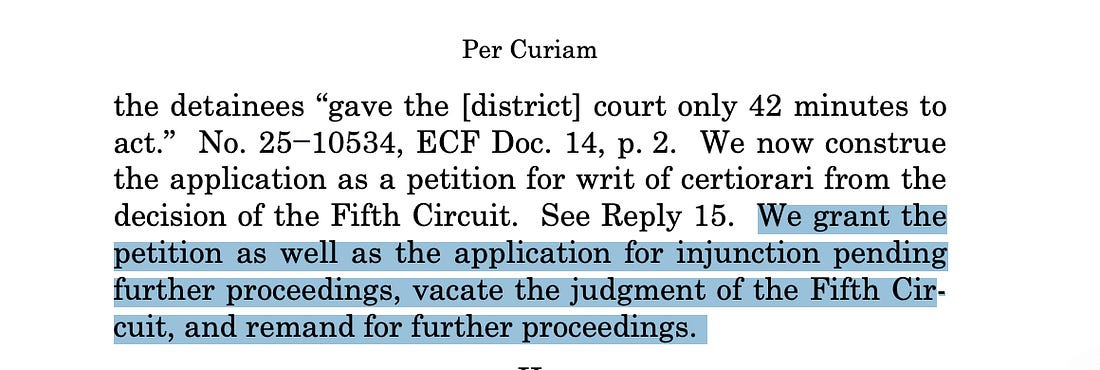

This was not a full decision on the merits of the case, which, when it happens, will determine whether Trump can use the Alien Enemies Act to deport alleged gang members. This decision was another of the type we’ve seen frequently since Trump retook office, an effort to prevent him from going ahead with a scheme of dubious legality while the courts determine whether that scheme is legal. The Court wrote, “To be clear, we decide today only that the detainees are entitled to more notice than was given on April 18, and we grant temporary injunctive relief to preserve our jurisdiction while the question of what notice is due is adjudicated.”

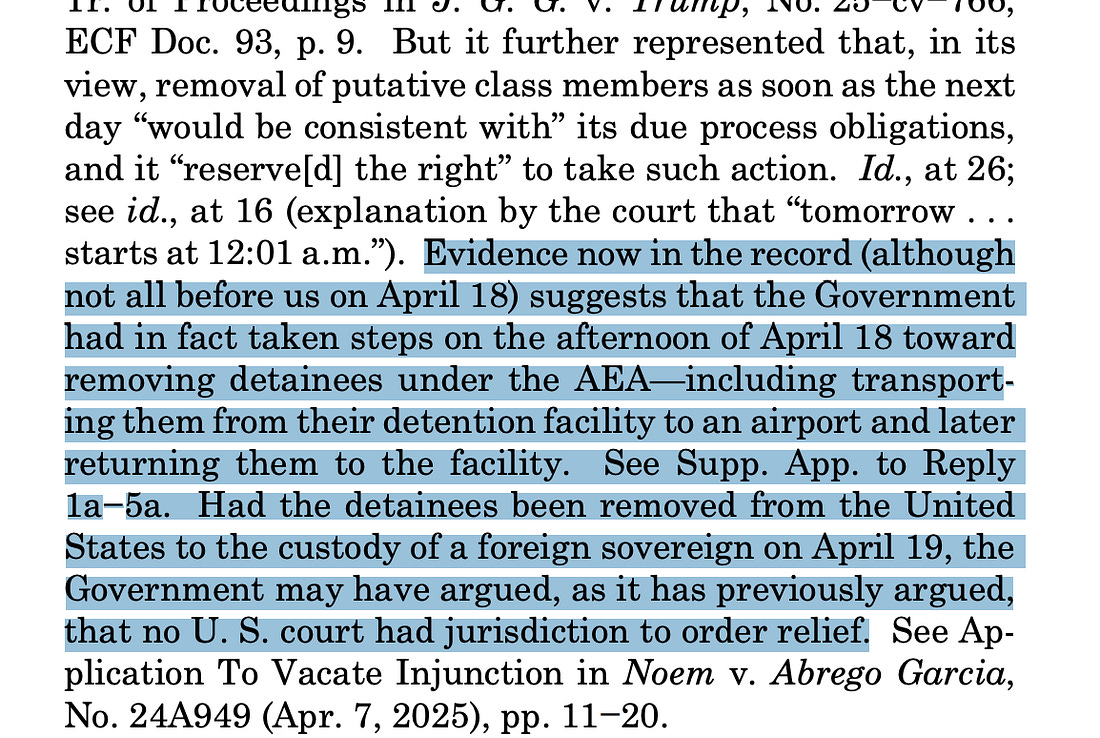

There are a couple of threads to pull there. First, the Supreme Court didn’t tell the government what it would have to do before deporting people in order to satisfy due process requirements. Second, they emphasized that they are granting the injunction because if they didn’t, the government would deport these people and then claim, as they have in the Abrego Garcia case, that once someone is out of the United States, even when our government is responsible for that, the courts no longer have jurisdiction to hear their cases. That’s as close as the Supreme Court ever comes to accusing the government of perfidy.

So, if the Supreme Court isn’t saying what the government must do to satisfy the requirement that aliens receive due process before being deported, who will?

The Court held that because it is “far removed from the circumstances on the ground” it is better for the Fifth Circuit to “determine in the first instance the precise process necessary to satisfy the Constitution in this case,” and they remand (send the case back to) that court to do so. That’s interesting because the Court is sharply critical of both the district judge and the Court of Appeals—almost to the point of suggesting they wouldn’t recognize due process if it slapped them in the face. But here, they do as they normally do; they are asking the lower courts to do their jobs, giving them the opportunity after the Supreme Court has reversed their prior decision to come into compliance with the law. That’s how the court system works.

To ensure that the Fifth Circuit gets the message, the Court offered some caveats, concluding that “The detainees’ interests at stake are accordingly particularly weighty” because the government didn’t refute the plaintiffs claim it was previously prepared to whisk them out of the country quickly and with no chance to go to court while also arguing in another case that “it is unable to provide for the return of an individual deported in error to a prison in El Salvador.” The Court directs the Fifth Circuit that “Under these circumstances, notice roughly 24 hours before removal, devoid of information about how to exercise due process rights to contest that removal, surely does not pass muster.” Now it’s up to the Fifth Circuit to set the bar the government must clear to provide due process, knowing it will be subject to review by the Court again after they do and that seven of the justices are testy about it. If they read the opinion, they’ll find a lot of guidance in it.

In its decision, The Court concluded that the government didn’t give enough notice, and the Fifth Circuit erred in refusing to provide relief. (Justice Alito, joined by Thomas in dissent, suggested that neither the district judge nor the Court of Appeals was wrong.)

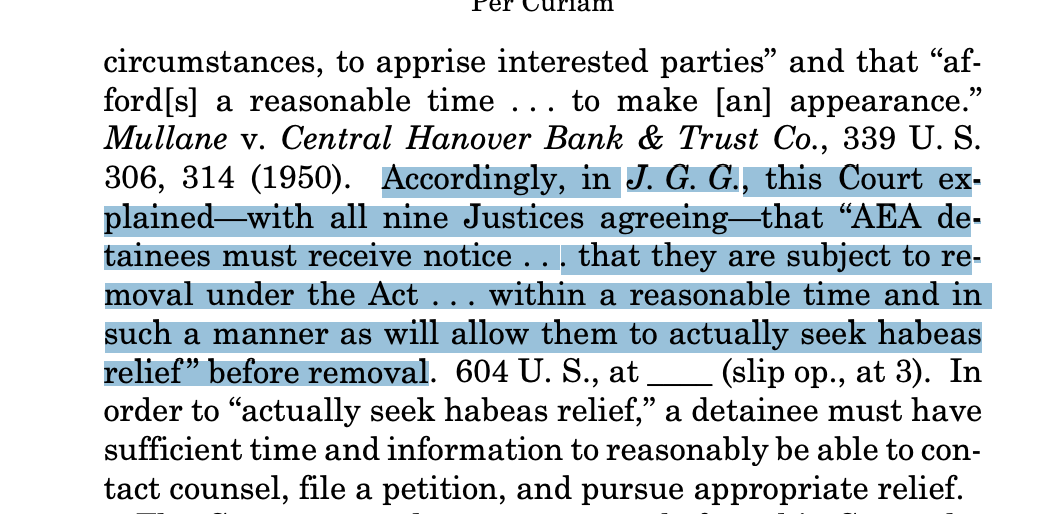

The Court also clarified what it’s talking about when it says due process is required:

“‘[T]he Fifth Amendment entitles aliens to due process of law in the context of removal proceedings.’”

“‘Procedural due process rules are meant to protect’ against ‘the mistaken or unjustified deprivation of life, liberty, or property.’”

“We have long held that ‘no person shall be’ removed from the United States ‘without opportunity, at some time, to be heard.’”

“Due process requires notice that is ‘reasonably calculated, under all the circumstances, to apprise interested parties’ and that ‘afford[s] a reasonable time . . . to make [an] appearance.’”

The Court underscored the fact that previously, all nine of the Justices unanimously agreed that aliens are entitled to due process. That came in the in the course of considering the government’s efforts to deport these people faster than the courts could intervene. The Court made it as clear as one has to when talking to a four-year-old, that “In order to ‘actually seek habeas relief,’ a detainee must have sufficient time and information to reasonably be able to contact counsel, file a petition, and pursue appropriate relief.” The government can’t deport people unless they have that opportunity. End of story.

The Court also directs the lower courts to move “expeditiously,” no lollygagging, pointing out that they have yet to rule on the merits issue—whether the government is entitled to invoke the Alien Enemies Act to conduct these deportations in the first place. Although Justice Kavanaugh, writing a concurring opinion, where he joined the majority, noted he would have jumped straight to that substantive issue (interesting in light of his willingness to play delay games and vote against jumping straight to the ultimate issue when Trump’s immunity from prosecution claim was going up and down on appeal). As it stands now, the Supreme Court can’t rule on that issue until the lower courts do their job and rule, and the Justices are making it clear they don’t want to see a lot of delay.

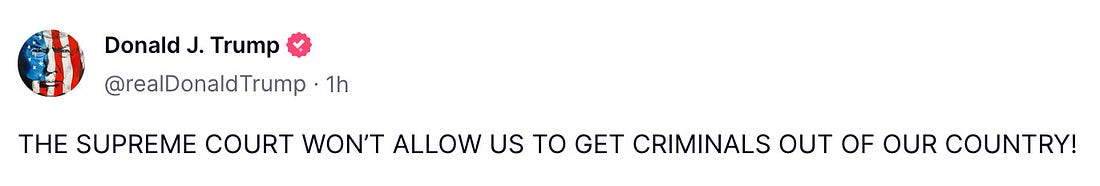

Trump had a reaction, of course.

If, as it appears, the Supreme Court is biding its time, giving Trump every opportunity to comply with the law while preparing to strike if he doesn’t, then Trump is making the case against himself. Just as his solicitor general told Justice Barrett during oral argument in the birthright citizenship case, this is an administration that doesn’t think