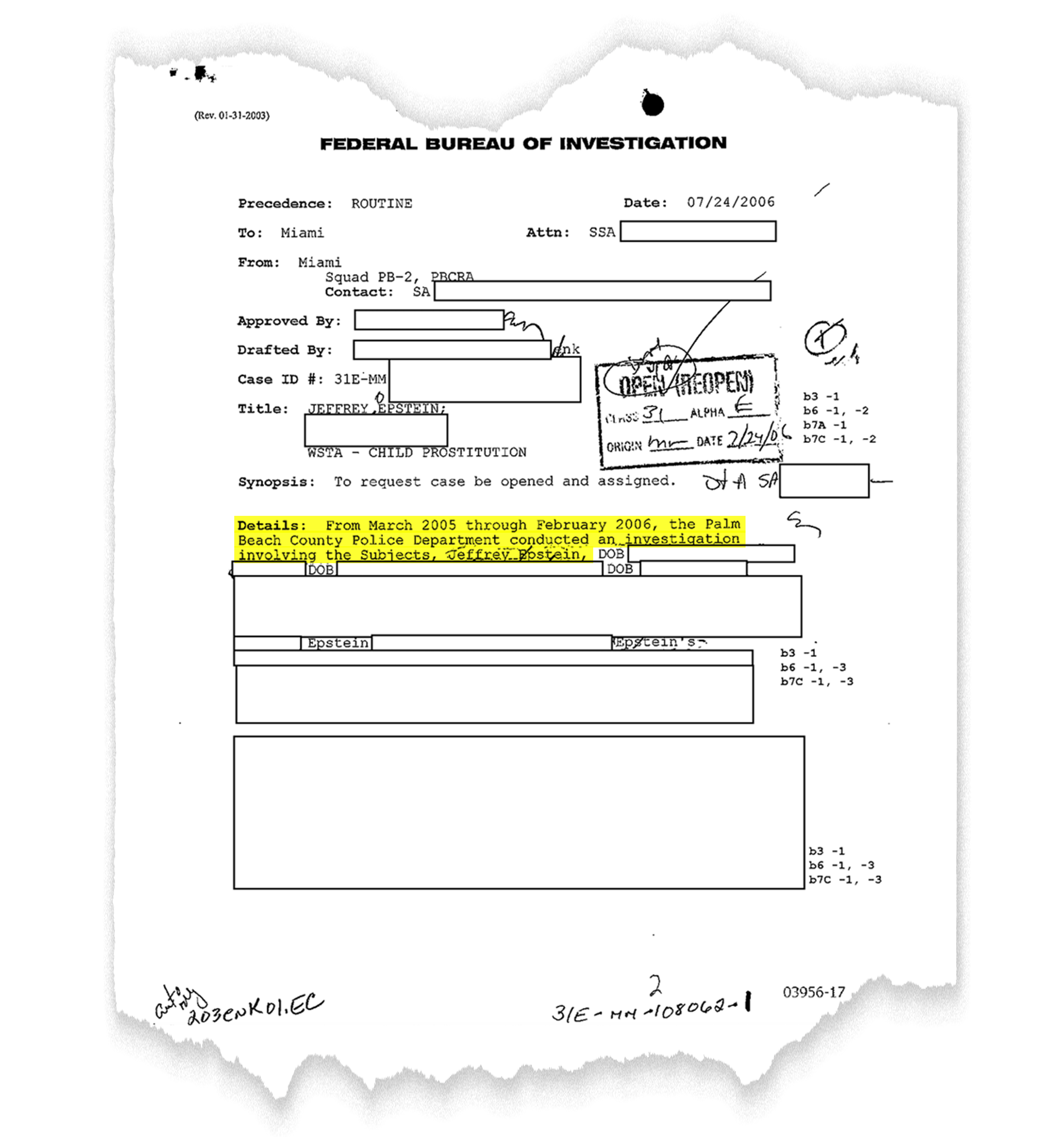

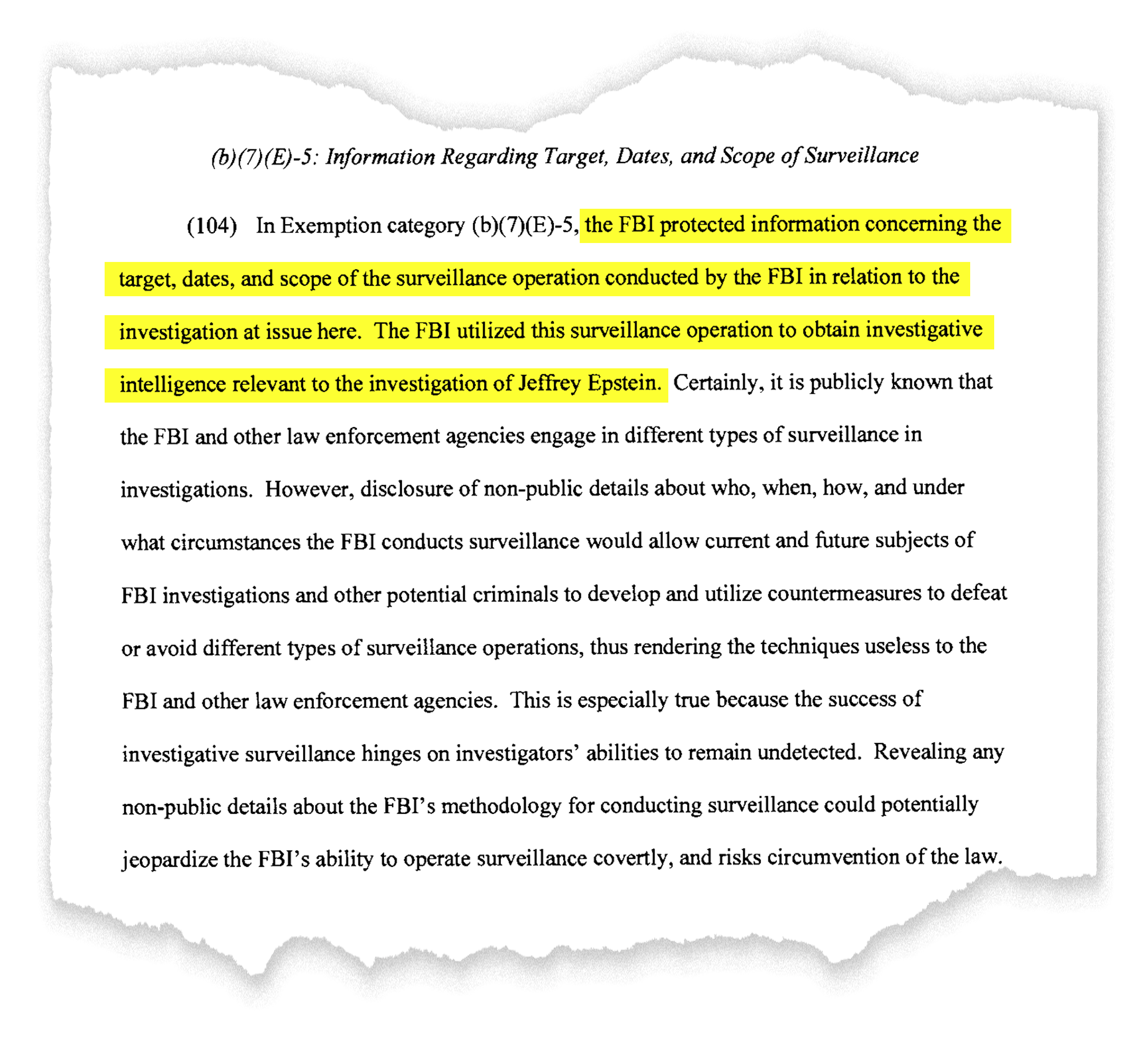

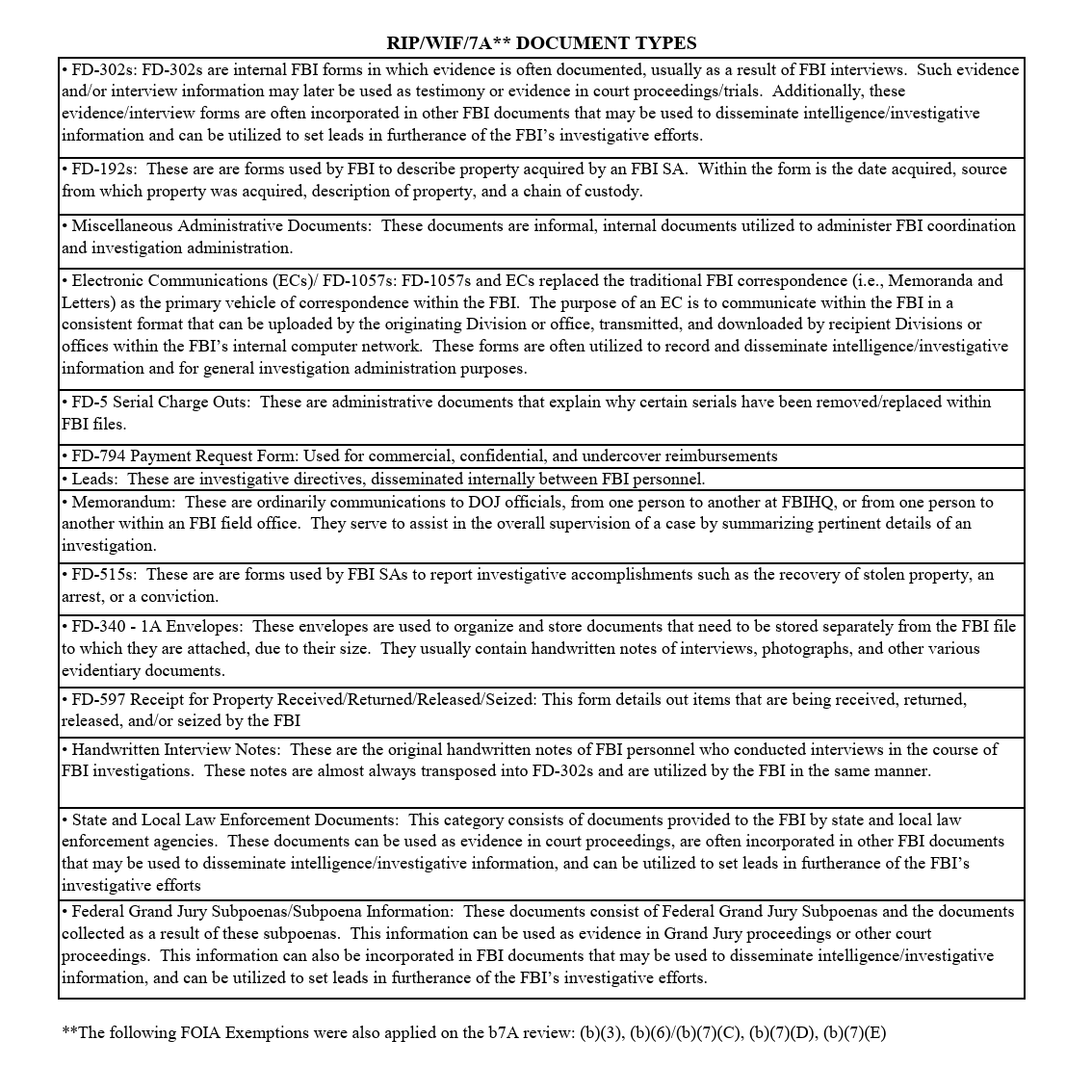

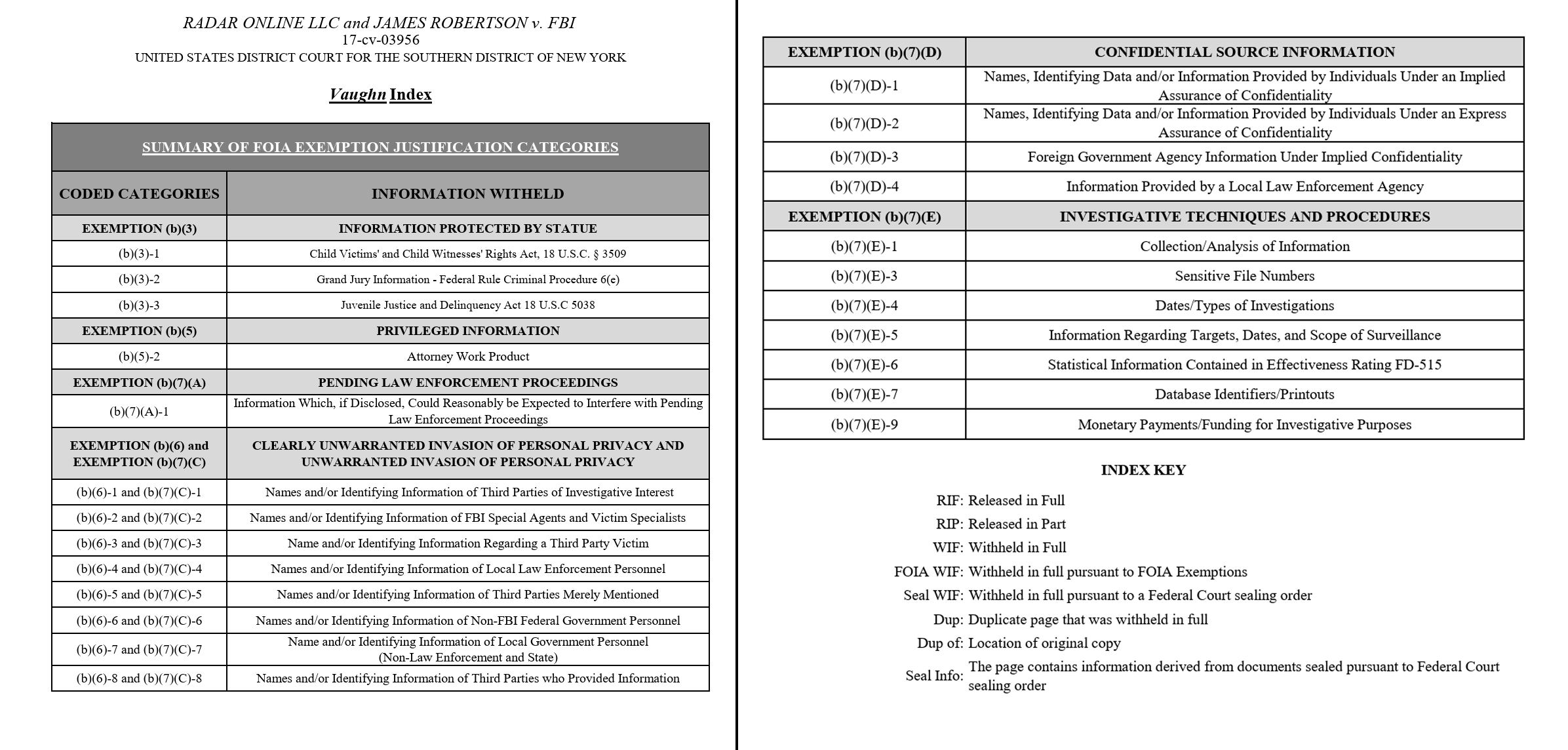

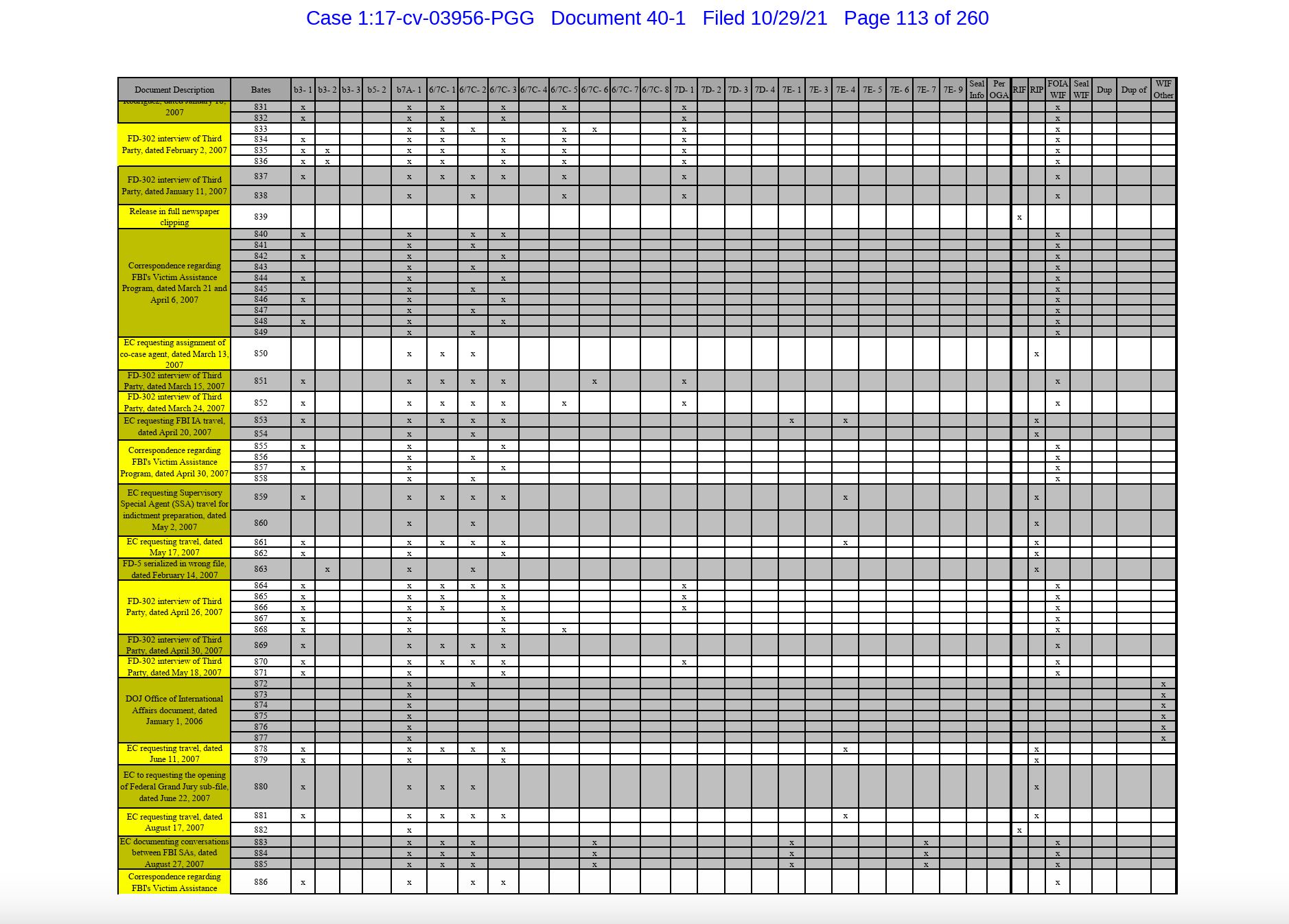

| Welcome back to FOIA Files! Another week, another deep dive into the Jeffrey Epstein saga that has engulfed the Trump administration. We know that the Justice Department and FBI amassed more than 300 gigabytes of data during the epic two-month search for all of the government’s documents on the disgraced financier and convicted sex offender. We know that the DOJ and FBI concluded in July that further disclosure of the Epstein files would not be “appropriate or warranted.” What we don’t know is what, exactly, is in the files. It turns out, some clues are buried in an under-the-radar, eight-year-old Freedom of Information Act case. I’ll explain. If you’re not already getting FOIA Files in your inbox, sign up here. Neither confirm nor deny? Really? | The intense secrecy shrouding the Epstein files dates back to President Donald Trump’s first term. Back then, the FBI blocked the release of documents from its investigation into Epstein. Since then a pretty interesting—and infuriating—chain of events has unfolded. It dates to April 20, 2017. That’s when James Robertson, an editor for The National Enquirer and RadarOnline, filed a FOIA request with the FBI seeking “all documents relating to the FBI’s investigation and prosecution of” Epstein. A week later, the FBI denied his request, saying that the bureau could neither confirm nor deny the Epstein records existed and, even if they did, Robertson’s request for records on third parties bumped up against two privacy exemptions. (They were the exact same exemptions the FBI used to justify redacting Trump’s name from the files, which I wrote about in last week’s edition of FOIA Files!) However, in its response, the bureau held out an option that was untethered from reality: It included a privacy waiver, and explained that Robertson must first obtain permission from the subject of his request—Epstein—before the FBI would even consider releasing documents about him. Ultimately, the FBI’s argument in denying the records boiled down to this: Epstein was never charged with a federal crime. Therefore the release of any FBI records revealing his name could “engender comment and speculation and carries a stigmatizing connotation,” according to the exemption cited by the FBI when it refused to release the documents. Robertson, who later co-authored a book about Epstein, sued the FBI a month later, arguing that the bureau was wrong in its decision to withhold the records. In October 2017, the FBI did start to release a sliver of its investigative files on Epstein. Ultimately, over the course of nearly three years, it processed a total of 11,571 pages that the FBI considered responsive to Robertson’s initial request. However, it released only about 1,200 pages, which were heavily redacted. The FBI posted those 1,200 pages in the bureau’s online FOIA reading room, The Vault. To be clear, the FBI wasn’t acting particularly generous or proactively transparent when it released this narrow set of Epstein documents to the Vault. It was forced to do that. Under the 2016 FOIA amendments, if an agency gets three or more FOIA requests on the same subject it is required to release the records to everyone. If there’s any doubt that’s why the FBI released those files, there’s the telltale series of numbers at the bottom of each page, which corresponds with the federal docket number of Robertson’s FOIA case. What’s surprising, though, is that the Epstein documents posted to the Vault are the very same documents that have been screenshotted and shared thousands of times on social media amid a torrent of renewed interest in the matter.  An “electronic communication” from an FBI agent dated July 24, 2006 requesting authorization to open an investigation into Jeffrey Epstein So what happened to the remaining 10,371 pages of documents not released by the FBI? Well, here’s where the plot thickens. The processing of the Epstein files ground to a halt in July 2019 when Epstein was indicted on federal sex trafficking charges. The FBI explained to Robertson and his attorney, Dan Novack, that it couldn’t release any further records on Epstein since the man was now being prosecuted. In particular, the department said that the remaining records would be withheld in their entirety due to ongoing law enforcement proceedings and because disclosure could impact Epstein’s ability to get a fair trial. But wait. A month later, Epstein died by suicide in his jail cell while awaiting trial. Wouldn’t the fact that the defendant was no longer alive mean that the documents could now, finally, be released? Not so fast. The FBI did release another 46 pages that it determined wouldn’t interfere with the ongoing proceedings (mainly news clippings), but it stopped there. The bureau’s FOIA team said that even though Epstein was dead and federal prosecutors dropped their case against him, records still needed to be withheld because of ongoing law enforcement proceedings. Fast-forward to July 2, 2020, when it became clear what the FBI meant. That’s the day Epstein’s former girlfriend and close confidante, Ghislaine Maxwell, was indicted on federal sex trafficking charges. Now, the FBI said in a letter to Robertson’s lawyer, it was required to withhold all of the Epstein files because the further release of any documents could interfere with Maxwell’s ability to obtain a fair trial and could potentially prejudice a jury. During the course of Robertson’s ongoing FOIA legal battle, Maxwell was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison. Novack argued once again that the documents should be released, this time since the case was resolved. But in a development that borders on the absurd, the FBI and the federal prosecutor on the case, Maureen Comey, argued against disclosure because Maxwell was appealing her conviction. (Last month, Trump fired Maureen Comey, the daughter of former FBI Director James Comey.) Also included in the docket was a declaration from Michael Seidel, the then-head of the FBI’s records office. He explained the bureau’s latest rationale for withholding Epstein files pertained to numerous sensitivities, such as the “surveillance operation conducted by the FBI...to obtain investigative intelligence” on Epstein.  A section from Seidel’s declaration describing the need for secrecy (page 47) If that information were revealed, Seidel said, it could “allow current and future subjects of FBI investigations and other potential criminals to develop and utilize countermeasures to defeat or avoid different types of surveillance operations.” (In last week’s FOIA Files, I reported that Seidel was essentially forced out of the FBI over Attorney General Pam Bondi’s botched rollout of the Epstein files in January.) Last year, a US District Court Judge ruled in favor of the government and agreed that the FBI didn’t have to release any additional Epstein records given Maxwell’s ongoing appeal. Novack has since appealed the decision to the 2nd Circuit Court of Appeals. Like other reporters, I’ve been scouring the RadarOnline docket in search of any details that might shed more light on the 10,000 pages the FBI withheld. Drawing on my own experience from filing nearly 200 FOIA lawsuits against government agencies, I know that when a case comes to a close, an agency is required to produce a so-called Vaughn Index (named after a 1973 court case), which describes the documents it withheld and redacted, and the justification for doing so. The Vaughn Index the FBI produced for RadarOnline is 170 pages—and it contains some pretty revealing details about what is hiding inside the FBI’s Epstein Files.  The types of records FBI withheld due to “ongoing enforcement proceedings.” Among other things that the FBI processed, but withheld, was: information provided by confidential sources, letters addressed to then-US Attorney for the Southern District of Florida, Alex Acosta (who cut a plea deal with Epstein in 2008 that saw him avoid federal sex-trafficking charges), subpoenas to MySpace, agents’ handwritten notes, photographs, grand jury subpoenas, intelligence analyses, and a wide-range of correspondence related to the FBI’s victim assistance program. And here is a detailed explanation of what was in other categories of documents the FBI redacted and withheld.  The categories of Epstein-related records the FBI partially redacted or withheld in their entirety. Even more intriguing, the index included correspondence with foreign government agencies, a large volume of subpoenaed phone records and a lot of bank records. Separately, the FBI created a spreadsheet that contains a detailed breakdown of the documents it processed. Importantly, it reveals that the FBI conducted 55 interviews with witnesses, victims and potential investigative targets between 2006 and 2008. The interview summaries, known as “302s,” and the names of all the interviewees were withheld with the exception of one, Alfredo Rodriguez, Epstein’s former butler, who was sentenced to 18 months in prison in 2012 for concealing Epstein’s “black book” during the federal probe.  A page from the Vaughn Index. The left hand column describes the type of records the FBI withheld (page 13) Something else that’s noteworthy from the Vaughn Index: the FBI’s investigation into Epstein remained active after he pleaded guilty to state charges of solicitation in Florida in 2008 and was released from prison in 2009. Some of the documents that were processed and withheld are from 2011, and include dozens of photographs, agents’ interview notes of third parties, and documents provided to the FBI by confidential sources. The FBI doesn’t typically close investigations. Usually, they keep a file open and continuously submit to that file. When the FBI does reach a formal conclusion in a case, they prepare what’s known as a “case closing memorandum.” There is no case closing memorandum in the Epstein Vaughn Index, which indicates that the case remained active. So, where does all this leave us? Even as Trump’s supporters, and now lawmakers from both sides of the aisle, continue to demand further disclosures in the Epstein Files, the Trump administration has made clear it has no intention of releasing any further materials. That’s why RadarOnline’s FOIA lawsuit might be the best shot, after all, of getting a glimpse inside the controversial records. There’s one potentially interesting twist on the horizon. Last month, Trump administration officials visited Maxwell in the federal prison where she’d been serving out her sentence. After two days of questioning, Trump wouldn’t rule out the possibility of issuing her a pardon. Last week she was moved to a minimum security prison in another state, raising further speculation about whether she might be freed. If Trump pardons her, RadarOnline’s FOIA case could become very interesting, yet again. But I wouldn’t hold your breath. It’s pretty clear by now that the FBI won’t part easily with those 10,000 pages. Got a tip about the Epstein files or a document you think I should request via FOIA? Send me an email: jleopold15@bloomberg.net or jasonleopold@protonmail.com. Or send me a secure message on Signal: @JasonLeopold.666. |