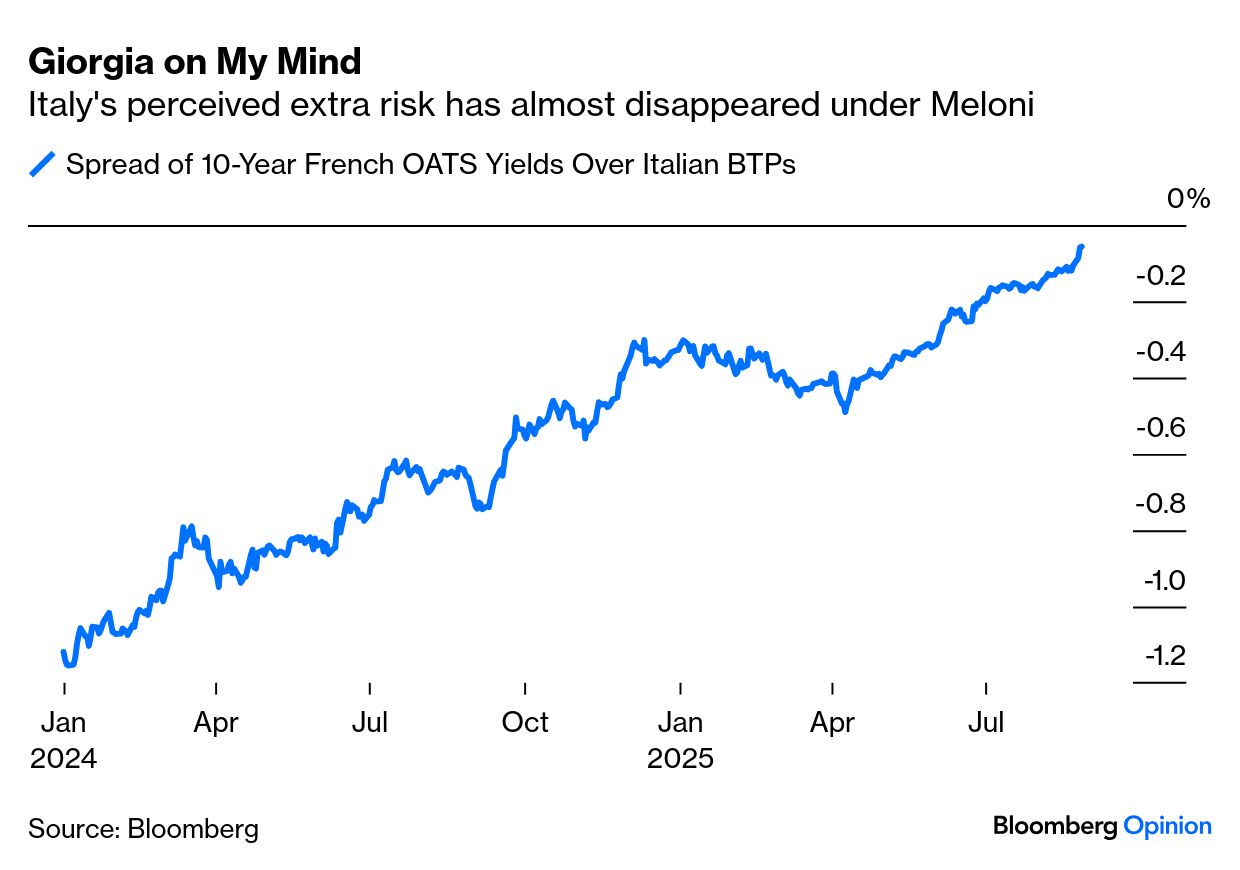

| After a nine-month respite, we need to start worrying about French politics again. The key chart, with trigger warnings for all those who lived through the euro zone sovereign debt crisis, is this one: The spread of 10-year French OATS over German bund yields is almost back to its highs during last year’s political crises: French stocks have resumed sharp underperformance of the rest of Europe: Points of Return covered President Emmanuel Macron’s failed gamble on snap elections, the three-way tie that logjammed the legislature, serious budget travails, and the resignation of Prime Minister Michel Barnier after failing to win a budget vote. With fiscal negotiations about to restart, his successor, Francois Bayrou, is calling a confidence vote Sept. 8 that he is likely to lose. Worse still, his finance minister warned in as many words that France might need help from the International Monetary Fund, awaking extremely unpleasant memories in the UK, which accepted a bailout in 1976. What next, and why should we care? The biggest argument not to worry comes from this chart, on the spread of OATS over Italian BTPs. Italy has long been the fiscal sick man of Europe, and markets were terrified when it elected Giorgia Meloni, from a party of the hard right, late in 2023. She seemed just as anti-European and dangerous as the National Rally’s Marine Le Pen, who was thwarted in last year’s parliamentary election but who has a good chance of winning real power soon. And yet the market has warmed to Meloni, and the risk premium for buying BTPs rather than OATS has almost disappeared under her tenure:  The Meloni experience suggests that a leader from the far right needn’t be so bad at all, if they’re in control (Meloni is more secure in her post than any Italian premier in a long time) and pragmatic. It’s not in the interests of Meloni or Italy to provoke a confrontation with the European Union, so she hasn't done it. Le Pen also has a history of ferocious Euro-skepticism, but she will not want to trigger a crisis as soon as her party finally reaches power.  Le Pen can look to Meloni for inspiration. Photographer: Anita Pouchard Serra/Bloomberg Bayrou’s budget proposals last month sounded even more unpalatable than the medicine Britain’s Labour party had to swallow 49 years ago. As summarized by Mizuho Securities, the premier wanted to save €43.8 billion ($51 billion) next year by: - Scrapping bank holidays.

- €5bn effort to curb social spending.

- No increase in 2026 pension payments.

- Cutting stakes in some companies.

Le Pen has already said that her party will vote no-confidence in Bayrou, leaving him very little room for maneuver. Prediction markets put his chance of losing at 90%. It’s unlikely that Macron, whose term lasts until May 2027 and cannot be forced to leave, will call elections straight away. If he were to call an early presidential contest, he’s term-limited, so that would amount to resignation; and he’s not the resigning kind. Jordan Rochester of Mizuho Securities in London puts the odds of what happens after the confidence vote at: - 70%: Name a new PM, who will likely continue to work on the budget (largely on the same lines as Bayrou).

- 25%: Call for snap legislative elections, given the political gridlock.

- 5%: Call for early presidential elections.

The market’s implicit judgment is that an all-out financial crisis (possibly involving the IMF) could come before a Le Pen premiership or presidency. But neither is imminent. Even though Bayrou has tried to force the issue, the odds favor yet more infuriating drift in Paris. |