London Design Festival highlights, Trafalgar Square sculptures, Aram exhibitions, plus outdoor seating in Birmingham

|

Wednesday 17/9/25

|

|

|

London

Paris

Zürich

Milan

Bangkok

Tokyo

Toronto

|

|

|

|

talk of the town

It’s a London Design Festival special, with the UK capital’s flagship industry event running until the weekend. It is headlined by exhibitions and installations across the city, including Paul Cocksedge’s sculptural temporary work in Trafalgar Square (pictured). We also visit an exhibition at Aram and look back at outdoor seating presented in Birmingham. Plus: London Design Award-winner Michael Anastassiades. First, it’s Nic Monisse on the importance of reflection.

|

|

OPINION: nic monisse

Life lessons

Industry award events can lend themselves to back-patting moments – a time to congratulate people for jobs well done and projects nicely finished. They can also be an opportunity to establish clear benchmarks for future work – a better ambition. But at this week’s London Design Awards, held at the new V&A East Storehouse during London Design Festival, the winners – who were acknowledged in four categories – bucked the trend.

Cypriot-born Michael Anastassiades (see ‘Words With...’ below) picked up the top prize, the London Design Medal, while Rio Kobayashi was recognised with the emerging talent award. Irish academic and activist Sinéad Burke won the design innovation medal and Norman Foster was acknowledged for lifetime achievement. In their acceptance speeches, the latter two broke from the typical self-congratulatory trend. While we were celebrating their bodies of work, both took time in their acceptance speeches to encourage reflection.

Burke, who advocates for inclusivity in design, made this clear from the dais. “If I can boldly ask anything of the designers in attendance, it’s that when you go back to your blueprints this week, you think about who isn’t yet included in your work,” she said, imploring the audience to consider everyone from the elderly and disabled to youth in proposed design solutions. “Figure out where they are and put them at the centre. We have a duty, an obligation and an opportunity.”

She was followed by Foster who, at 90 years of age, skipped the stairs and leapt onto the stage. In his speech, he recalled recently being asked to give guidance to graduating students. “It’s the same advice I give to myself,” he said. “Stay a student – be curious, dare to challenge, to question, to be a good listener, to not be afraid of failure, to take risks but above all, be humble. I have tried with varying degrees of success and failure to stand by those rules. Here, in my 91st year, I confess that I’m still working at it.”

It’s in these moments, hearing speeches like these, that it’s easy to recall the Socratic adage that the unexamined life is not worth living. In our personal lives, certainly, a lack of introspection and critical thought can make for a meaningless existence. But the same could be said of a designer’s practice (or any professional work) too.

Without stopping to reflect on who’s missing from the picture, as Burke suggests or, without continuing to question “how” and “why”, as Foster says that he continues to do, there’s a risk that design is distilled down to an occupation that’s only about delivering beautiful objects or architectures devoid of a deeper meaning. The unexamined practice, perhaps, is not worth practising. Reflecting can ensure a work has purpose, that it can deliver social good and enhance quality of life for users – that’s the power of good design. Burke and Foster prove that it’s an award-winning approach too.

Nic Monisse is Monocle’s design editor. For more from the London Design Festival, tune in to ‘Monocle on Design’ on Monocle Radio.

|

|

SIGMA  MONOCLE MONOCLE

|

|

IN THE PICTURE: ‘Beyond Foam’ at Aram

Material gains

Are you sitting comfortably? If the answer is yes, there’s a strong likelihood that the seat on which you perch contains some form of foam. Unfortunately, as effective as it might be in cushioning hard surfaces, conventional foam made from polyurethane is responsible for millions of tonnes of landfill every year. Enter EcoLattice, a research start-up by Yash Shah that is developing substitutes made from environmentally friendly materials that are 3D-printed into a lattice foam – a process that allows for relatively rapid production and affordability.

“I’m on a mission to reinvent [materials] until they do more with less,” says Shah. “It’s all about solving real problems with a little rebellion and a lot of curiosity.” As part of London Design Festival, Shah is teaming up with Covent Garden-based furniture dealer Aram to stage Beyond Foam, an exhibition that features eight emerging UK designers who used EcoLattice’s foam replacement to create pieces that aim to nudge consumers into rethinking the materials we interact with on a daily basis.

‘Beyond Foam’ runs until 1 November as part of London Design Festival at Aram, 110 Drury Lane, London.

aram.co.uk; ecolattice.uk

|

|

WORDS WITH... Michael Anastassiades

Leading light

It has been a busy, award-winning few years for Michael Anastassiades. The Cypriot-born, London-based designer picked up a prestigious Compasso d’Oro from the Milan-based Association for Industrial Design in 2020 and was distinguished as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) last year. This week he also won the London Design Medal, which was presented during the city’s namesake design festival. The award is a recognition of more than three decades of outstanding work from his studio, which commands international attention for its refined approach to lighting design and partnerships with brands, including Flos (pictured).

Tell us about your design ethos.

My work is about layering. You have to introduce layers otherwise your work will remain very superficial. If you’re addressing only one small thing then there is no chance that the project will have longevity or relevance. You need to keep people excited about something that they see every day. Excitement should grow if something, from furniture to lighting, is part of your house – every time that you use it should trigger your imagination.

How is this ethos expressed in your work?

I’m able to express it through my own brand. We never put any protective layers on our products. The brass, for instance, is unfinished, so it develops its own patina over time. You can polish it if you want. This allows you to build a relationship with the object.

What design movement has influenced you the most?

Modernism is what I’m drawn to. But at the same time, it doesn’t mean that I am absolute in that relationship. I allow space for everything else to exist too.

What’s a recurring source of inspiration?

I love art. It really nourishes my mind. I’m fascinated by people’s creativity. I tend to venture to a museum, exhibition or gallery every weekend. It doesn’t matter whether they’re famous institutions or small ones – I believe that every place has something special to offer if you’re open to it.

When you started your studio, you also worked as a yoga teacher to supplement your income. How did this other career affect your work?

Everything you do in life affects the next thing that you try. Yoga definitely was and is a big part of my life. It taught me to approach what I do from an outside perspective. Whenever I feel that I’m too invested in design, it allows me to step back and be critical of what it is that I’m doing for myself.

What’s a priority for you and the industry going forward?

Design is deeply personal and it’s also a dialogue. As a designer, you have something to say with your products and it’s an opportunity to trigger somebody’s imagination. There has to be an open door for the dialogue to pass through and people should want to engage with it.

|

|

from the archive: Birmingham outdoor seating

Sitting pretty

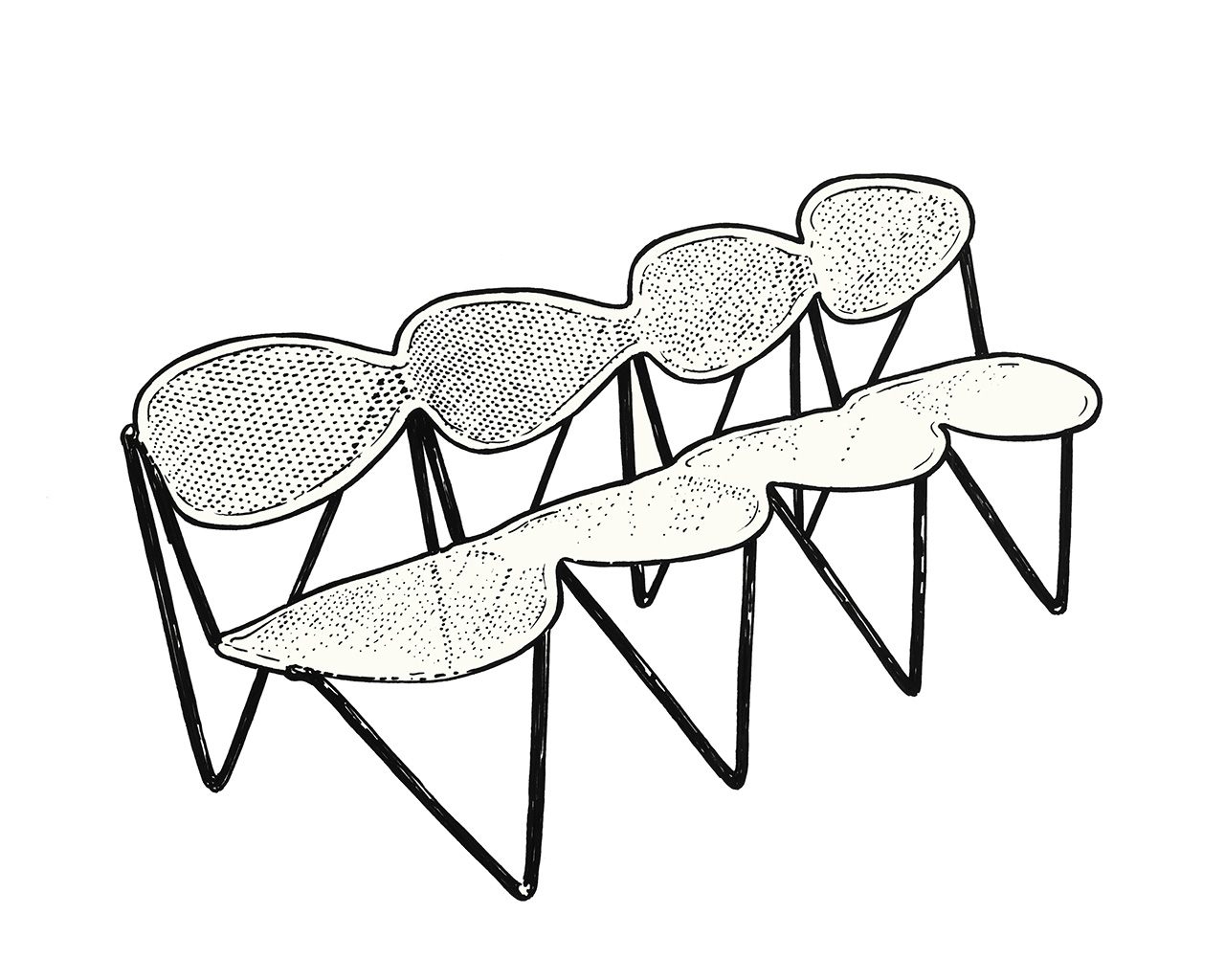

Brits visiting the London Design Festival might be pleased to know that they are continuing a proud tradition – even Winston Churchill was a fan. In 1944, the British government started planning for postwar economic recovery and founded the Council for Industrial Design (today’s Design Council), a charity with the responsibility of organising exhibitions. It did so with gusto, setting up blockbusters such as the Festival of Britain in 1951 as well as smaller, regional events, including the Exhibition of Outdoor Seats in Birmingham in 1953. The latter produced this four-person bench with a steel-mesh seat and hairpin legs.

Britain’s public parks have been fitted out with slightly sturdier benches, and the designer of this prototype has been lost to history. But the history of the Design Council is a reminder of the central role that design fairs have always played in promoting both economic growth and prettier cities. The companies at London Design Festival today would do well to give more attention to public space – and reissuing this bench would be as good a place as any to start.

|

|

around the house: keeling collection

Chairs and graces

The 20th century saw the production of several now-famous architect-designed chairs, with the likes of Oscar Niemeyer, Jean Prouvé, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Pierre Jeanneret all lending their signature to iconic designs. But what of architecture-inspired seating? That’s a question that London-based designer Joe Armitage is addressing in partnership with British furniture manufacturer Ercol. Launching during London Design Festival, Armitage has produced the Keeling Collection: a dining chair, footrest and armchair inspired by the Denys Lasdun-designed structure of the same name.

“The Keeling Collection began as a question: What would a chair for a Denys Lasdun building look like?” says Armitage. “Lasdun’s theory of architecture as landscape, with its interplay of horizontal and vertical elements, became the foundation for both the form and the structure of the design.” The result is a series defined by its use of blackened ash plywood. Sitting on a stainless-steel structure, the armchair is completed by walnut armrests and upholstery in wool by UK heritage brand Tibor, with a custom textile that reinterprets the façade of Keeling House – a striking tribute to one of London’s most revered post-war architects.

View the Keeling Collection by Joe Armitage at the ‘Grain Pile’ exhibition curated by Max Radford Gallery. It’s on show at Old Clerkenwell Fire Station until 22 September 2025 as part of the London Design Festival.

|

|

| | |