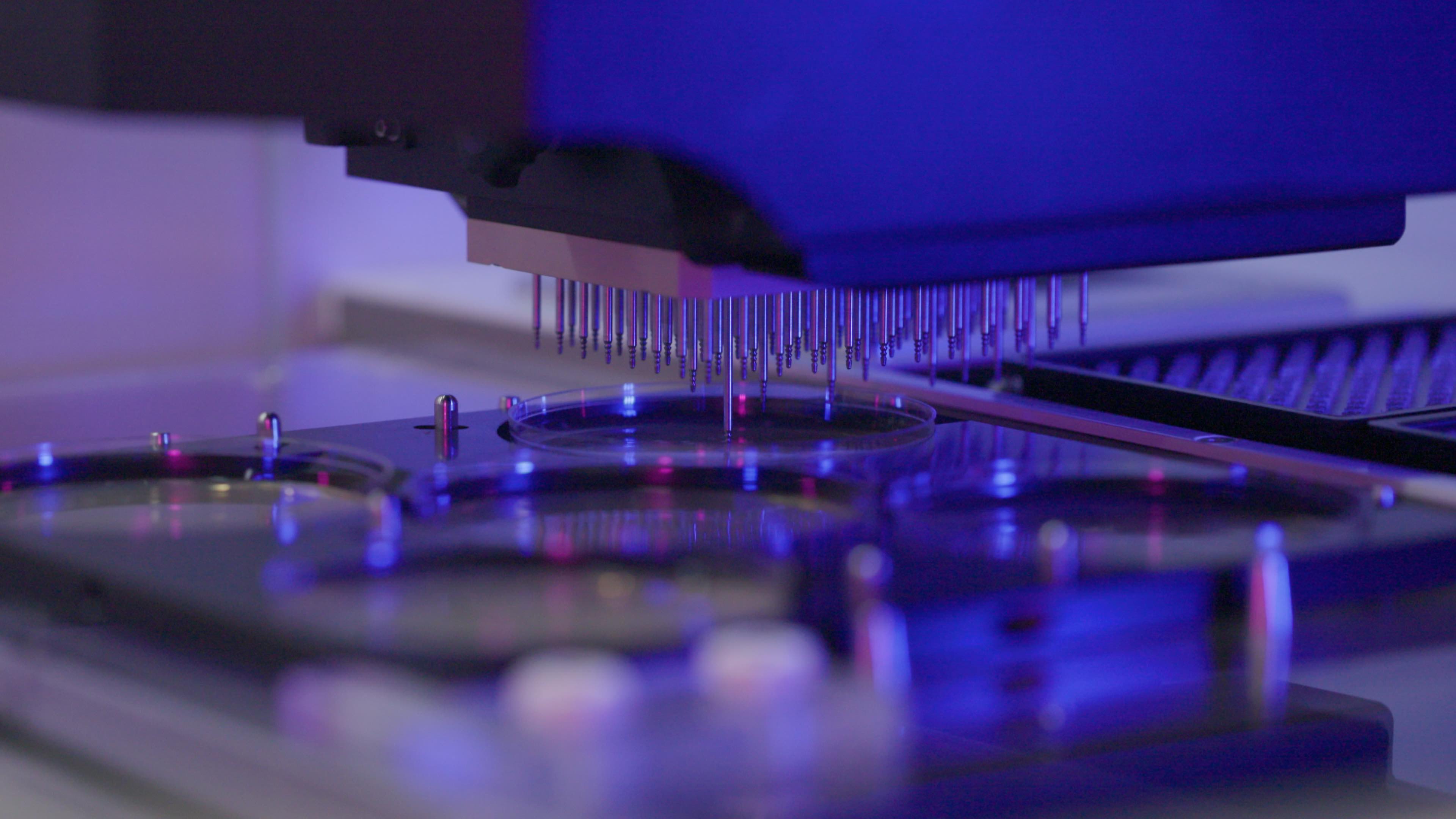

| A California company has created an engineered protein that could be used to help blind people see — or even build a next-generation brain implant. The discovery came from Science Corp., which was founded by Max Hodak, the former president and co-founder of Neuralink, Elon Musk’s brain implant company. Science is building several things, including a device to restore vision and a chip that plugs into the brain using living neurons instead of wires. The new protein, he explained, could help with both pursuits. That could be a boon to Science, and also to science. Less than 10 days after a preprint paper was posted describing the work, several academic groups and two companies reached out to see if they can use the protein, Hodak said. The protein is an opsin, which creates an electrical current when it’s hit with light. It’s part of a nascent field called optogenetics, where researchers use light to control brain activity. Neurons communicate through electricity, so by genetically modifying brain cells to make them produce electricity-generating opsins and then shining a light on the cells, researchers can make the neurons fire in specific ways, causing the brain to do particular things. Just by shining a light on the brain of a mouse, researchers have made their whiskers move, made them happy, and triggered hallucinations.  Petri dishes with bacteria containing custom-made proteins that scientists test to see how well they respond to regular light. Source: Science Corporation But up until now, the light required to activate an opsin had to be very powerful, like a laser or strong LED. That limited its use — lasers can generate heat, damaging the tissue. So scientists could only stimulate a small number of neurons, limiting their ability to influence brain activity. Science’s scientists were able to create an opsin that generates electrical current when exposed to regular indoor lighting, which is much lower energy than lasers. This could allow researchers to build devices that would stimulate many more cells at the same time. No one else has figured out how to create an opsin like this that responds so well to indoor light, Hodak said. The protein could also help people with eye diseases, and Science plans to test it for that purpose within two years, Hodak said. The idea would be to design a gene therapy for diseases that damage the cells that convert light into electricity for the first step of vision, such as macular degeneration, retinitis pigmentosa or Stargardt disease. The cells behind the damaged ones, which are one step closer to the brain, could be genetically modified to produce the new opsin and make them sensitive to normal light. This might help a person see better. “That could unlock something like really next-level performance if that works as anticipated,” Hodak said. Science could also use the opsins in its experimental electronic implant, which connects to the brain using engineered neurons instead of metal or polymers, as other companies are using. If those engineered neurons have the new opsins, they could also be stimulated with low-energy light to change what the brain is doing. — Ike Swetlitz |