| Forwarded this email? Subscribe for more |

|

| By Coleman Hughes |

If you’ve been following American politics for the past five years, you may have noticed an unhealthy pattern: The left, which controls most cultural institutions, uses soft power to shape them in an ever more progressive direction. The right, which controls few cultural institutions but does possess political power, passes vague and heavy-handed policies intended to undo the left’s handiwork (and then some).

Core to this pattern is the fact that the left tends to view the institutions it controls as politically neutral when, in fact, they are stamped throughout with their own sacred values. The right, in turn, tends to see their scorched-earth responses as justified by a sense of powerlessness over the leftward direction of American culture.

Perhaps nowhere has this pattern been more perfectly illustrated than in the fight over depictions of slavery in our national museums.

Free Press Free Week ends Sunday, October 12. Don’t lose access—upgrade your subscription today. |

The fight began when President Donald Trump issued the executive order “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History” on March 27. The executive order was intended to fight the “corrosive ideology” that I call “neoracism” in my book—an ideological outgrowth of critical race theory that demonizes whiteness, elevates blackness, and argues that America is white supremacist in its very DNA.

As the order explained, this ideology “seeks to undermine the remarkable achievements of the United States by casting its founding principles and historical milestones in a negative light,” and reconstructs America’s “unparalleled legacy of advancing liberty, individual rights, and human happiness” as “inherently racist, sexist, oppressive, or otherwise irredeemably flawed.”

Starting about a decade ago, neoracism began to sweep through America’s elite institutions. As I explained in a recent essay, journalistic outlets began to blame just about everything on the legacy of slavery, including Excel spreadsheets, gynecology, tipping, mass incarceration, the Second Amendment, prison labor, Jack Daniel’s whiskey, fine dining, abortion bans, coffee, the word cakewalk, and the obesity crisis.

The same ideology began to show up in public and private school classrooms all around the nation. Parents complained about woke teachers taking the curriculum into their own hands and indoctrinating students with concepts like “white privilege,” “systemic racism,” and “gender fluidity.”

One of the many things Trump has done to fight this strategy is direct the Smithsonian Institution’s Board of Regents to “prohibit expenditure on exhibits or programs that degrade shared American values, divide Americans based on race, or promote programs or ideologies inconsistent with federal law and policy.”

It does not take a linguist to understand that this order is vaguely worded and bound to produce confusion—one man’s “divisive” ideology is another man’s common sense. Nor does it take a constitutional expert to understand that Trump does not have the authority to force the Smithsonian to do anything. By law, the Smithsonian is run by a Board of Regents, and that board is composed of the vice president, the chief justice of the Supreme Court, three senators appointed by the president pro tempore of the Senate, three House representatives appointed by the Speaker of the House, and nine citizens appointed by a joint resolution of Congress. In other words, Trump can’t just take a wrecking ball to the institution without violating the separation of powers and the rule of law.

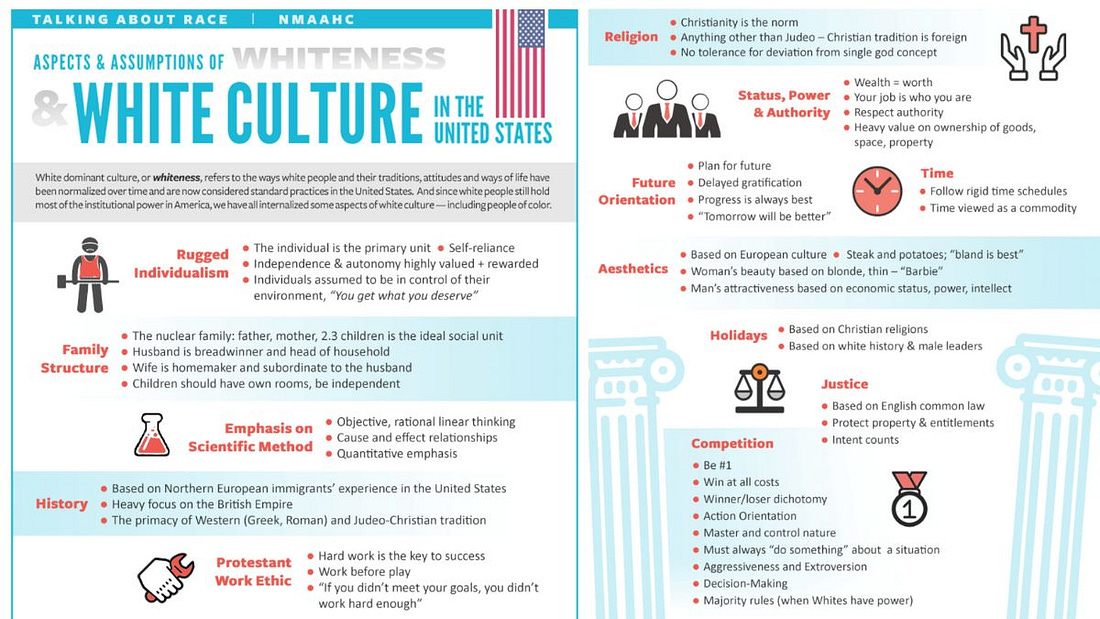

But despite its flaws, Trump’s executive order did not just fall out of the sky. It is a reaction to recent events. It cites, for instance, a shameful episode from 2020—during the height of the hysteria touched off by the death of George Floyd—when the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture featured a graphic on its website entitled “Aspects & Assumptions of Whiteness & White Culture in the United States.” The graphic argued that values like “self-reliance,” “the nuclear family,” “objective, rational linear thinking,” “work before play,” and “delayed gratification” were elements of white culture, rather than healthy values that Americans of all races have an equal claim to.

|

There is nothing more racist than the assumption that these values are the special purview of whites. Yet the graphic stayed up for six weeks and was removed only after significant backlash. Such a mistake could happen only at an institution that was blindly captured by woke ideology.

If Trump’s aim were simply to roll back this sort of woke, racist nonsense, then I would get behind it without a single caveat. But Trump rarely limits himself to a reasonable response, and this was no exception. In August, he posted on Truth Social:

The Smithsonian is OUT OF CONTROL, where everything discussed is how horrible our Country is, how bad Slavery was, and how unaccomplished the downtrodden have been—Nothing about Success, nothing about Brightness, nothing about the Future.

Trump’s post is all the more unreasonable given the origin story of the African American history museum itself. It was created and funded via an act of Congress in 2003, at a time both chambers were controlled by Republicans, and signed into law by President George W. Bush. By law, the museum must have “permanent and temporary exhibits documenting the history of slavery in America” as well as other aspects of African American history. This was all a bipartisan effort—not an example of the left forcing something down the right’s throat. If Republicans had a problem with it, they could’ve thwarted it at the time.

So, given that we all agreed to create a museum with a permanent exhibit on slavery—an effort I absolutely support—how exactly is the museum supposed to depict slavery without emphasizing how bad it was? Like war and famine, there is no intellectually honest way to cover slavery without the “badness” sort of jumping out at you. To take just one specific example: How does one cover the Middle Passage in a way that makes it look anything but evil to the modern eye?

This is not to say the Smithsonian’s slavery exhibit is without flaws. As John McWhorter pointed out in The New York Times earlier this year, the exhibit could have done more to highlight African participation in the transatlantic slave trade. He is echoing an argument made some 15 years ago by Henry Louis Gates Jr., who wrote an infamous New York Times op-ed called “Ending the Slavery Blame-Game.” In it, Gates pointed out that, for whatever reason, Africans are the one group of people that have mysteriously escaped history’s harsh eye despite being enthusiastic participants in the transatlantic slave trade.

“The sad truth is that without complex business partnerships between African elites and European traders and commercial agents, the slave trade to the New World would have been impossible, at least on the scale it occurred,” he wrote.

The backlash to the op-ed was fierce. As Gates put it: “People wanted to kill me, man.”

If Trump’s aim were simply to roll back this sort of woke, racist nonsense, then I would get behind it without a single caveat. But Trump rarely limits himself to a reasonable response, and this was no exception.

The Gates fiasco was part of a broader problem with how the narrative of slavery is told by progressives so as to shine a spotlight on bad behavior by white people and conveniently leave out the entire multiracial and global history of slavery. Gates argued that “we need to get some distance from the binary opposition we were raised in: evil white people and good black people. The world just isn’t like that.”

How many American kids are taught that the major Native American tribes of the Southeast owned slaves, and all five of them sided with the Confederacy at the start of the Civil War? How many are taught that America’s first post-independence war was the result of the long-standing trade in white European slaves by the pirates of the North African coast? How many kids are taught that far more (white) Russian serfs were emancipated in the 1860s than American slaves were emancipated in the same decade? How many learn that as many Africans likely died being marched by their African enslavers from the interior of the continent to the coast as died on the Middle Passage?

In progressive spaces, there is little appetite for the aforementioned facts, as they stray off message—the message being, as Gates put it, “evil white people and good black people.” And therein lies the aspect of progressive history that is tailored toward increasing racial division in the present, where whiteness is seen as an original sin, and blackness the cause of every misfortune: It’s not so much about what is said, but about what is left unsaid.

The Trump administration has accurately diagnosed a problem area in American culture. But its attempt to fix it should not focus on minimizing the ugly facts of American slavery. Instead, it should focus on broadening the scope of facts that we allow into the conversation. In this way, Americans can have a more complete, more accurate, and less racially divisive picture of our own history—without compromising the truth.