| The US stock market closed Wednesday at an all-time high. Gold has also never been more expensive, and for the first time costs more than $4,000 per ounce. Meanwhile, both the excitement and the apprehension over the vast sums companies are investing in artificial intelligence intensifies; those big investments seem ever more circular, as the AI giants pour money into each other. These things are related. Beyond their causal links, they also help explain each other. The rally in gold — which gains when people are pessimistic — casts a different light on stocks, the choice of optimists. Denominate US stocks in gold rather than the dollar, and they have been in decline ever since the dot-com bubble burst 25 years ago. Stocks everywhere else have done far worse: Precious metals are an inflation hedge. Yet the most direct market inflation forecasts, from swaps and from bond breakevens, agree that inflation will stay within the ranges of most of the last two decades: Metals suggest something different. Precious metals (including palladium, platinum and silver) have outstripped industrial metals to a record extent in Bloomberg’s indexes. They’ve only previously rallied like this during extreme alarms over the economy, such as the pandemic and the Global Financial Crisis: How do we justify buying stocks when gold signals alarm? Michael Wilson, equity strategist at Morgan Stanley, set out a fascinating bull case for stocks this week that sadly also reads like a bear case for society. He starts with the point that both stocks and gold are hedges against inflation, which is likely to increase as the Fed seems to be locked into dovishness (as evidenced by the minutes of the latest Federal Open Market Committee meeting) and that stocks now appear to be far cheaper. He draws this comparison with the peak for the S&P 500 in gold terms back in 2000: This was a time of real wage growth, high productivity, balanced budgets and a better affordability backdrop for everyday needs like housing, health care, education, food and energy — largely the opposite of the past 15-20 years. Today, the ratio is almost 70% below the peak from 25 years ago. Stocks were much more expensive in 1999-2000 than they are today… because they were pricing in much stronger real growth that proved to be unachievable.

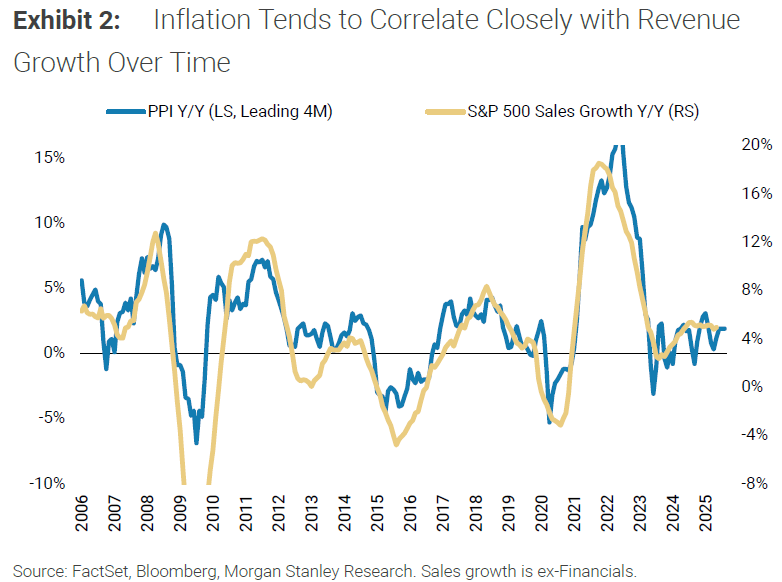

There are many measures on which stocks look almost as expensive as in 2000, but Wilson offers counterintuitive signs that they offer value. Taking the median stock (not the average for the overall index), S&P 500 stocks’ free cash flow yield is nearly treble that of 2000: Free cash flow involves subtracting capital expenditures from overall cash flow, so it’s encouraging that massive AI spending hasn’t dented it for the average company. For the overall index, dominated by the companies splurging on AI, it’s a different story. Its FCF yield is also back to the 2000 level. Other stock markets offer far better value: This neatly illustrates that the capex boom makes it hard to call stocks cheap. It’s also necessary to be forgiving about the record US profit margins. Over time, they tend to mean-revert, rising when capital has the upper hand, and falling when labor is ascendant. Of late, they just rise. While prospective earnings multiples are roughly back where they were in 2000, margins are much higher: If those margins are now sustainable, then it’s much easier to justify a higher multiple of earnings. Wilson provides a measure of the S&P 500’s forward p/e divided by the profit margin. On that basis, stocks are much cheaper than 25 years ago. The other way to look at this is that if profit margins were to revert to their long-term average of a little over 7%, then this measure would be right back where it was in the run-up to the millennium. Wilson suggests that margins will be helped by operational leverage as companies that have slimmed down their workforce take in more revenue. Higher margins, all else equal, tend to mean higher prices, and they would be aided by inflation, which is correlated with sales and gives firms greater cover to raise prices:  This analysis isn’t reassuring. If 2000 was about a surfeit of optimism, this is almost exactly the opposite. Optimism now is predicated on rising inflation. That’s not what people want. Last year’s US election swung more than anything else on price rises; the Biden administration was not forgiven for losing control. Trump 2.0 has taken dramatic action on many fronts, but not against inflation. Indeed, tariffs and pressure for lower rates are more or less the exact prescription to make inflation rise. The latest CBS News poll suggests that people have noticed: To be clear, it’s still the economy, stupid. Immigration and crime, justifications for sending troops onto the streets, are dwarfed in importance by jobs and inflation: The bull thesis might well be right. But if companies enjoy a circular boom in AI spending, and keep their wide profit margins, while inflation buoys their pricing power and revenues while giving investors little choice but to buy into them, the chances are that the electorate won’t be happy. The bullish narrative sounds a lot like an intensification of all the trends of the last few decades that left people so angry in the first place. |