|

|

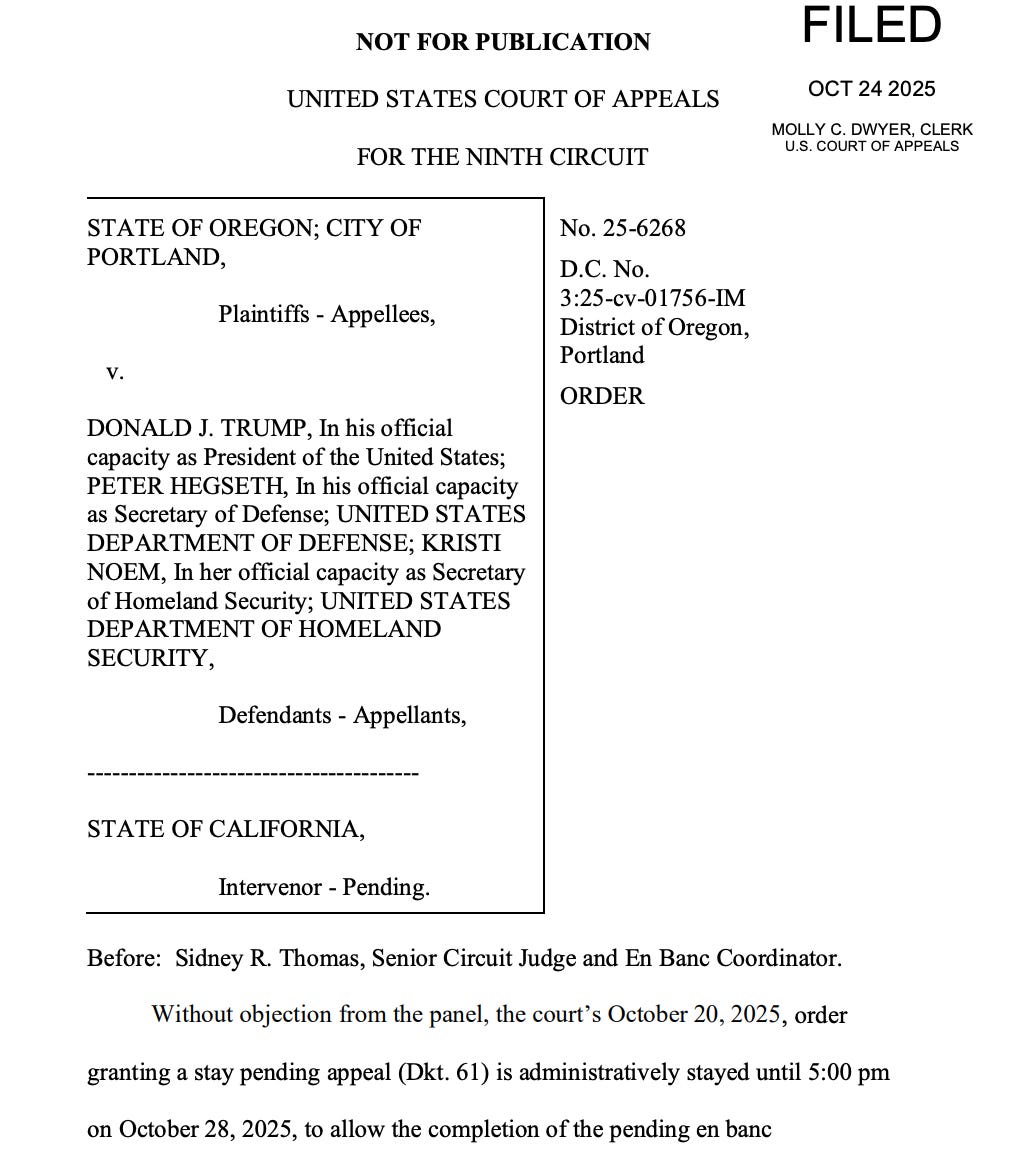

Last night, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reinstated, at least for now, Federal District Judge Karin Immergut’s first temporary restraining order, which prohibited the Trump administration from deploying the Oregon National Guard in Portland. It had been set aside, but the Circuit Court has put it back in place while determining whether the court will rehear the panel’s decision en banc.

The technicalities of the legal procedures here are intricate, but the bottom line is that it’s a setback, at least temporarily, for the Trump administration.

How did we get here? On Monday, a Ninth Circuit Panel ruled 2-1 that Trump could send National Guard troops into Portland. We discussed that decision here if you want a refresher. The majority ruled that “After considering the record at this preliminary stage, we conclude that it is likely that the President lawfully exercised his statutory authority,” and declined to interfere with Trump’s ability to send troops into Portland. The state initiated the request for reconsideration of that decision.

The stay will remain in effect until October 28 while the judges on the Ninth Circuit determine whether the full court will revisit the panel decision. This is the sort of administrative stay courts use to freeze the status quo briefly when they’re deciding what to do next and doesn’t suggest how they may end up ruling. The order says explicitly, “This administrative order expresses no views on the merits of this matter and is not a reconsideration of the earlier stay order.” But it does confirm there is a process taking place among the judges to consider the en banc request, and that it was not dismissed out of hand. They note that the administrative stay was imposed “[W]ithout objection from the panel.”

Interestingly, though, on Thursday, the state of Oregon filed a letter brief with the court, advising of what the state characterized as “a material factual error by defendants on which the panel relied to grant a stay pending appeal.” The panel ruled in the administration’s favor because it had demonstrated “a colorable inability to execute federal law”—one of the preconditions the president must find exists before he can federalize National Guard troops. The state says that DOJ’s argument was contradicted by material DOJ turned over to the state in discovery Wednesday evening, and that representations DOJ made in court previously were false:

DOJ told the court that protests had forced the redeployment of 115 Federal Protection Service (FPS) officers, about 25% of the nationwide force, of DHS employees responsible for protecting federal buildings, to Portland.

At oral argument in the matter, DOJ emphasized that having the 115 FPS officers deployed away from their posts to Portland was unsustainable for the government. Counsel for the administration was asked whether all 115 of the officers remained in Portland. The response was that “some” had returned home, but “many” remained in Portland.

The state claims that in the discovery DOJ produced, it admitted that the “115 FPS officers have never been redeployed to Portland” and that “only a fraction of that number was ever in Portland at any given time before the President’s directive.”

Unless the government can explain the discrepancy satisfactorily, the court will likely want to inquire into the source of the misrepresentation. Deliberate false statements made to a court by a lawyer carry serious consequences. If it turns out that the government did, in fact, misrepresent the facts in court, that will not help the government’s position as the Ninth Circuit considers whether rehearing en banc is appropriate. The panel could withdraw its opinion if one of more of the judges in the original majority believes this new information changes the outcome of the appeal, or the en banc court consider the updated evidence if it proceeds.

Judge Immergut had also imposed a second injunction, preventing the deployment of Guard troops from other states in Oregon. That remains in place, although the administration has asked the court to dissolve it and a hearing on the issue was scheduled for Friday morning. The state of Oregon argues that the factual inaccuracy also impacts that matter, making the administration’s efforts to send Guardsmen from one state to another even more suspect.

The Ninth Circuit is the largest court of appeals in the country, with 29 active judges. It is customary for judges to take senior status rather than retiring, and to continue to hear cases to keep the court’s caseload manageable even after their replacement has been confirmed by the Senate. Because of its size, the Ninth Circuit uses a randomly selected panel of 11 judges to decide en banc cases, rather than having all active judges participate, which is the practice in other circuits. During his first term in office, Trump reshaped the court with 10 appointments, transforming what had been the most liberal court in the country for decades. President Biden had the opportunity to appoint eight judges to the court, leaving the balance at 16 judges appointed by Democratic presidents to 13 appointed by Republicans, although that, of course, isn’t always predictive of how judges will rule.

Senior Judge Sidney R. Thomas, who sits in Montana, signed the administrative stay as the en banc coordinator for the case, but we don’t know which judges have been assigned to the panel and will be making the decision about whether the panel’s decision will be permitted to stand or be subject to further review.

The Trump administration has already moved to stay the court order in Chicago that prevents them from deploying the National Guard there. The City responded promptly and the administration has now replied. A number of amicus briefs have been filed as well. This is the same procedural posture we so frequently see the Court issue shadow docket rulings in, permitting or denying a stay in an unsigned opinion without much, if any, guidance as to the basis for their legal ruling. Given the importance of this issue and the heavy criticism of the way the Court has been using the shadow docket recently, expect a great deal of attention to be paid to how they resolve this case. We’ve seen the Court move quickly when it has a mind to, and there is no reason it couldn’t schedule this matter for oral argument promptly.

The Founding Fathers were against standing militias and certainly didn’t contemplate the deployment of military troops against American citizens on American soil. The Posse Comitatus Act has long prohibited that. It will be up to the Court to determine whether a president is permitted to make up emergencies that allow him to skirt the Act, opening up the potential for unprecedented militarization of our country.

Where it starts is never where it ends with this president. With the midterm elections at hand, giving Donald Trump the open-ended ability to declare an emergency with no evidence to support its existence and deploy the military to stoke fear and intimidate voters would be a dangerous development.

No matter what happens, we won’t be intimidated. It’s never too early to register to vote or make sure your registration is still active. This is a good time to make sure you have identification, including proof of citizenship, in case the administration succeeds in imposing more rigid requirements for voting. Above all, talk with the people around you and remind them that if our right to vote wasn’t powerful, they would not be trying to take it away from us. Whatever it takes, we need to make sure we vote in 2026.

If you find value in this kind of clear, experience-driven legal analysis, I hope you’ll consider a paid subscription to Civil Discourse. Your support means that I can devote the time and resources it takes to write the newsletter.

We’re in this together,

Joyce