|

|

|

|

In the mid-1600s, France developed the first overarching theory of how the global economy could work in its favour. All-powerful finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert pioneered its protectionist policies, tripling French import tariffs to make foreign goods prohibitively expensive. Sound familiar? Nearly four centuries later, many aspects of this model of “mercantilism” have been revived by Donald Trump’s tariffs of mass disruption.

In the first of an epic two-part series, Steve Schifferes from City St George’s, University of London, charts the rise and fall of globalisation, explaining how first Britain and then the US took on the role as the world’s economic top dog. Critically, he warns that for all globalisation’s faults, the world is a more unstable place when there is no such dominant power. And in part two, he will offer a chilling view of what the world’s financial future could look like, now the American century of global dominance is drawing rapidly to a close.

Until the onset of industrialisation in the 17th and 18th centuries brought artificial light and factory shifts, the idea of getting your eight hours of sleep was unusual. Most people didn’t sleep through the night, instead going to bed with the Sun and waking during the night for a couple of hours of activity. Now, studies suggest this might be one way to deal with insomnia.

And if you’ll be watching the next instalment of Celebrity Traitors tonight, keep an eye out for telltale clues from the “villains”. Research suggests that people tend to sweat when they are lying or under excessive pressure.

|

|

Mike Herd

Investigations Editor, Insights

|

|

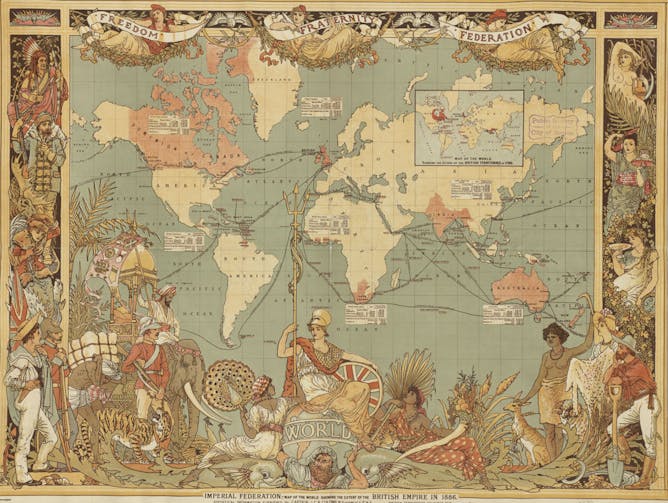

A world map showing the extent of the British Empire in 1886.

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center, Boston Public Library/Wikimedia Commons

Steve Schifferes, City St George's, University of London

In each era of globalisation since the mid-17th century, a single country has sought to be the clear world leader – shaping the rules of the global economy for all.

|

Albert Joseph Moore/Shutterstock

Darren Rhodes, Keele University

There’s a reason you sometimes wake up in the middle of the night.

|

Alan Carr worried about how his ‘sweating problem’ would affect his Traitors performance.

BBC/ Studio Lambert/ Euan Cherry

Adam Taylor, Lancaster University

The body have specific sweat glands are only activated when we’re in stressful situations.

|

World

|

-

Edward White, Kingston University

Environmental stress systematically activates the psychological vulnerabilities that drive criminal behaviour.

-

Richard Hargy, Queen's University Belfast

The states are high, so the Trump administration is trying to change voting laws, while both sides gerrymandering to give them an advantage.

-

Fumihito Gotoh, University of Sheffield

Takaichi has pledged to revive Shinzo Abe’s economic vision of high public spending and cheap borrowing.

|

|

Politics + Society

|

-

Kaigan Carrie, University of Westminster

Mental ill health was the leading cause of prison officer absence in the year to June 2025.

-

Madeline-Sophie Abbas, Lancaster University

The home secretary has the power to remove a person’s British citizenship if they consider it ‘conducive to the public good’.

|

|

Arts + Culture

|

-

Laura O'Flanagan, Dublin City University

Abou Sangaré’s performance is raw yet restrained, suffused with a sense of vulnerability that makes it impossible to look away.

-

Ian Varley, Nottingham Trent University; Philip Hennis, Nottingham Trent University

Friendship. Fitness. Fun. Walking football has it all – at a pace that suits everyone

-

Rebecca Wynne-Walsh, Edge Hill University

These tales of woe and mystery have young readers becoming amateur sleuths.

-

Dylan O'Driscoll, Coventry University; Birte Vogel, University of Manchester; Eric Lepp, University of Waterloo

By systematically tracking changes in murals over time, we have gained profound insights into the dynamics of peace and conflict.

|

|

Business + Economy

|

-

Fumihito Gotoh, University of Sheffield

Takaichi has pledged to revive Shinzo Abe’s economic vision of high public spending and cheap borrowing.

-

Jan Wilcox, University of Westminster

Whether a new tenant or an existing tenant, it has never been more important to keep abreast of new developments in the law.

-

Styliani Panetsidou, Coventry University; Angelos Synapis, Coventry University

As individuals, it’s easy to overlook the power we have when it comes to our finances.

|

|

Environment

|

-

Colm O'Shea, UCL; Mark Maslin, UCL

Wind power offers a large financial benefit to UK consumers.

|

|

Health

|

-

Ian Varley, Nottingham Trent University; Philip Hennis, Nottingham Trent University

Friendship. Fitness. Fun. Walking football has it all – at a pace that suits everyone

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

|

|

10 September - 29 October 2025

•

Southampton

|

|

|

|

| | | |