| | Congressional Republicans are divided over whether to curb the White House’s control of energy proje͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ |

| |   Washington DC Washington DC |   Detroit Detroit |   Riyadh Riyadh |

| Energy |  |

| |

|

- GOP’s permitting split

- Gas M&A fires up

- EVs in reverse

- Turbine backlog

- Saudi’s China push

Oil prices fall while pressure on Carney rises. |

|

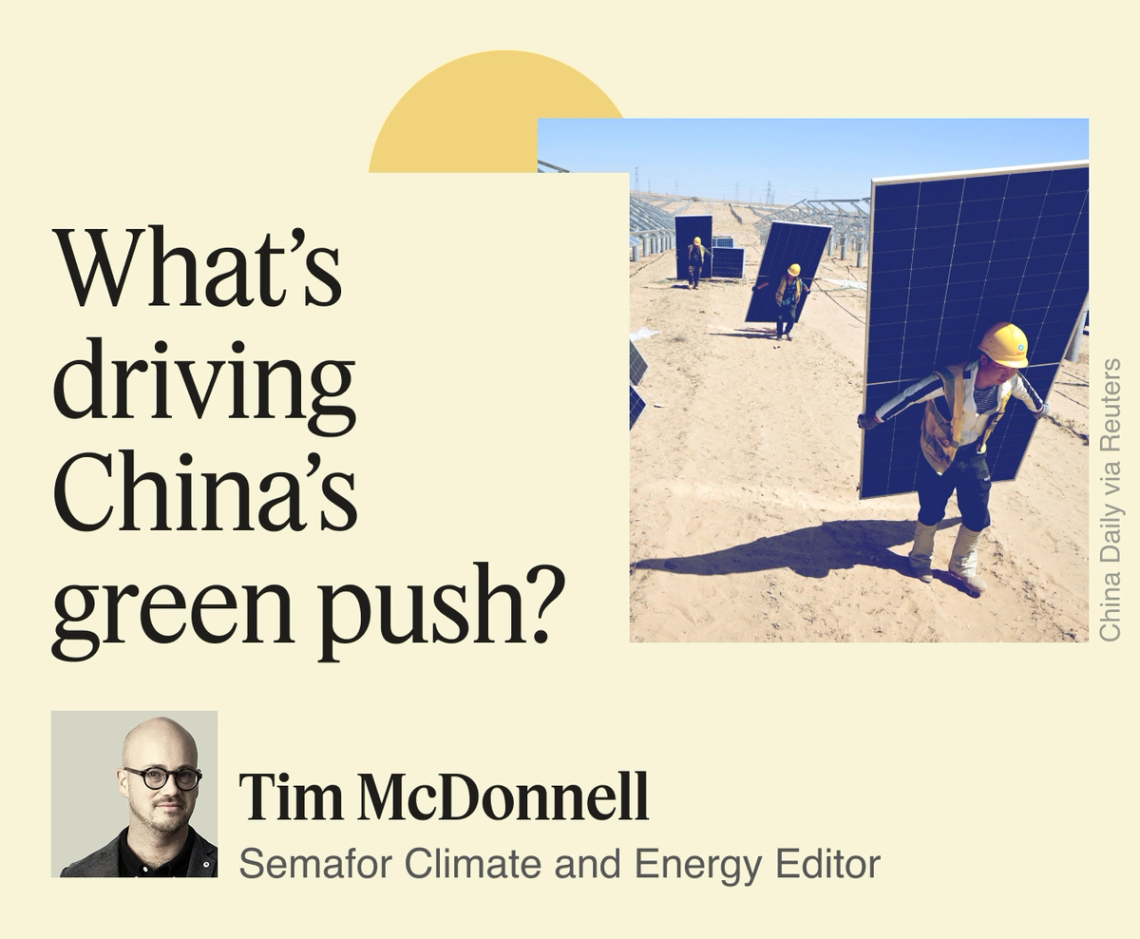

China’s energy transition continues to defy a simple narrative. There’s no shortage of mind-boggling statistics about the country’s energy sector: It consumes one-third of global electricity, manufactures far more solar panels in a year than the US has installed in total, etc. But a new one that stood out to me recently was the finding by Australian economists that since 2023, Chinese firms have directly invested more than $180 billion in green tech projects and factories outside the country, mostly in the global south. This number tells a story about how China is finding new ways of leveraging its energy resources to project geopolitical power. Although Chinese officials have savvily picked up on the Trump administration’s withdrawal from global climate politics as a chance to position themselves as environmental power brokers, the country’s race to dominate clean tech supply chains was never really about emissions. It’s about breaking free of US-controlled fossil fuels, while borrowing some pages from the petrostate playbook in service of China’s own overseas ambitions. As Heatmap’s Rob Meyer observed, “how [any] country approaches its near-term decarbonization goals depends on how it understands and relates to the Chinese government and Chinese companies.” Ultimately, a focus on decarbonization when it comes to the energy transition misses the point — countries want cheaper and more predictable electricity, and increasingly find China the only viable supplier for the means of producing it. It’s not only climate policy that’s inextricably linked to China, but increasingly energy security policy as a whole. Whether this happens to add up to a benefit for the climate remains uncertain; the Breakthrough Institute argued last week that China’s self-presentation as a cutting-edge green “electrostate” is a mirage that conceals its ongoing deep reliance on cheap, dirty coal. That view is shared in the White House; Richard Goldberg, until recently a senior White House energy adviser, told me recently that the Trump administration views China’s green claims “more like an information op, trying to throw us off of the actual types of power sources that we need to compete and win.” Yet, there’s another new stat worth noticing: Coal and gas-fired electricity generation in China fell for the first time this year since 2015. So Beijing’s efforts may not be just greenwashing after all. At the scale China operates, small changes in the energy trendline amount to huge volumes of emissions and money changing direction, globally. Just look at the progress China is making on nuclear fusion, an area Trump is also keen to control. So whatever’s really driving China’s green push, no one can afford to ignore it. |

|

Rep. Bruce Westerman, R-Ark. Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images Rep. Bruce Westerman, R-Ark. Bill Clark/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty ImagesUS lawmakers’ latest attempt at fixing the country’s dysfunctional energy permitting bureaucracy is inching forward this week, but disputes over the bill’s limits on executive power could dim its prospects. The Republican-backed SPEED Act attempts to accelerate the federal environmental impact review process by imposing limits on when such reviews are required and how they can be challenged in court. But to win some support from Democrats, the bill also limits the ability of federal agencies to revoke already-issued permits, which some Republican allies of President Donald Trump worry could impede his campaign against offshore wind farms (even though the bill is backed by the US Chamber of Commerce and the American Petroleum Institute). On Monday, the House Rules Committee said the full chamber can vote on amendments to curtail those limits on executive power, but it’s not clear the bill can survive without them — and if it does, it will face even tougher scrutiny next year in the Senate. |

|

Jon Shapley/Houston Chronicle via Getty Images Jon Shapley/Houston Chronicle via Getty ImagesMerger and acquisition activity in the fossil fuel industry will likely shift next year from oil-focused megadeals to smaller ones focused on gas, analysts said. Big Oil went through a number of high-profile contractions in the last two years, like ExxonMobil’s $60 billion purchase of Pioneer. Next year, as oil prices fall, there will likely be less interest in acquisitions, Wood Mackenzie analysts wrote in a new report, amid a broader pullback on spending by oil companies that could also cut into share buyback programs. US gas assets, however, are looking more attractive as the Trump administration leverages LNG exports in trade negotiations, and as gas demand for powering AI data centers grows. “Strategic and infrastructure investors are pursuing integrated platforms” that link upstream gas wells, pipelines, and export facilities “into unified value chains,” analysts at consulting firm PwC wrote in a separate report. |

|

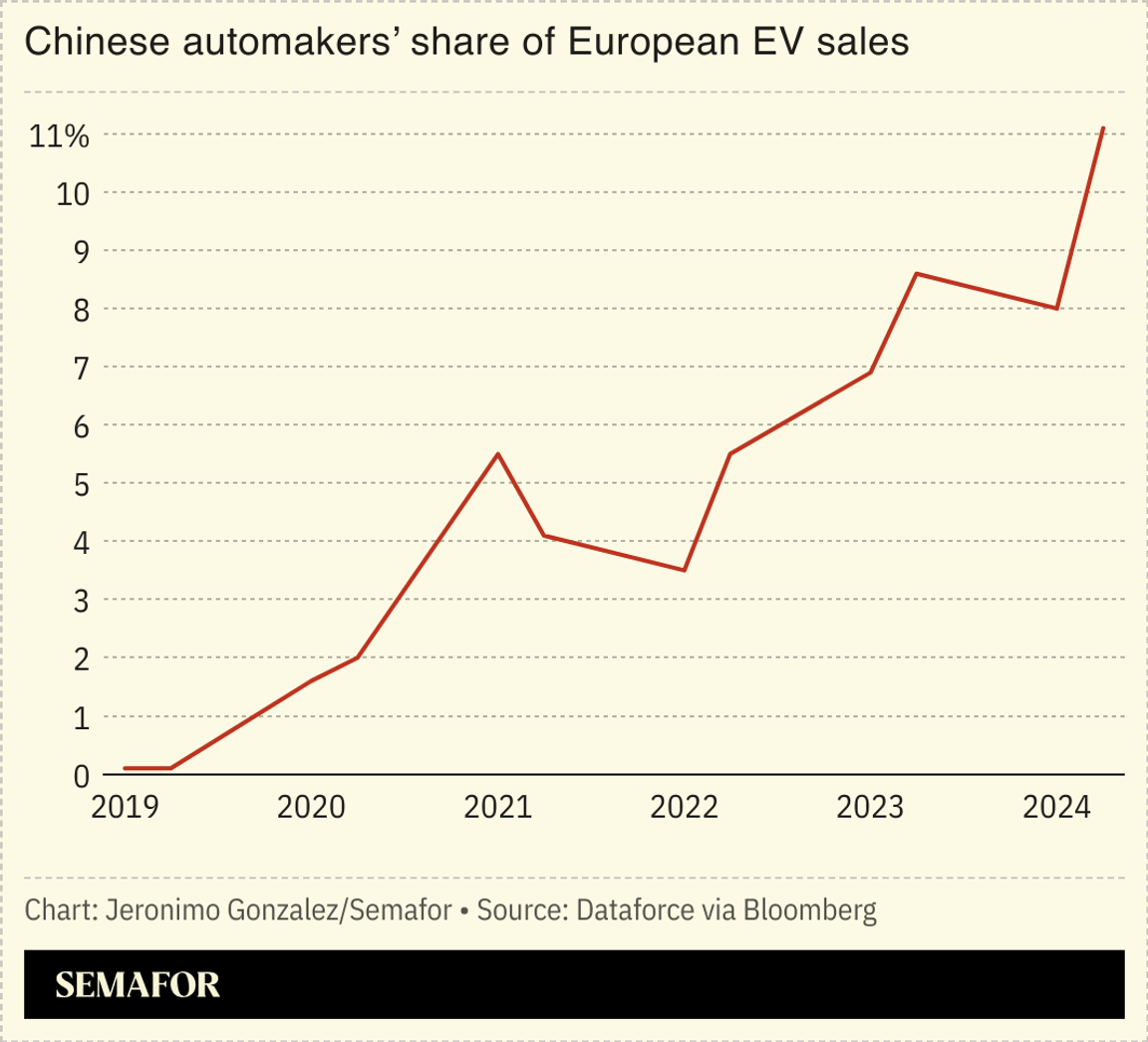

Major carmakers are delaying efforts to pivot to electric vehicles as they come under pressure from Chinese rivals and shifting political priorities. Ford dropped plans for an all-electric truck, accepting a $19.5 billion writedown, while Volkswagen is expected to extend its investment in gas-driven cars. Chinese models dominate the global EV market, and the US has dropped EV-purchase incentives, making it “all but impossible” for Western carmakers to give up the better profit margins available on internal combustion vehicles, The Wall Street Journal reported. Canada, the EU, and the UK are also rethinking their EV mandates. But firms also want to avoid falling behind technologically, and “it will be difficult to do both,” the Journal noted. |

|

Backlog of orders for gas turbines that GE Vernova expects to face by the end of this year, which will take the company into 2029 to fulfill. Gas turbines are in increasingly high demand for data centers and other large power users. GEV is ramping up its factory capacity in the US and Europe, but CEO Scott Strazik told investors he expects to be sold out of gas turbines (typical utility-scale ones are around 500 megawatts) by the end of next year through 2030. And as prices for in-demand turbines have risen, so too have the company’s fortunes, with revenue for its electrification division projected to grow about 25% this year and 20% the next. |

|

Yuan Hongyan/Reuters Yuan Hongyan/ReutersSaudi Arabia is accelerating its push into clean power — spanning solar, wind, and hydrogen — both at home and abroad. ACWA Power, the giant backed by the kingdom’s sovereign wealth fund, plans to deploy $20 billion in capital annually over the next five years, 60% of that domestically, CEO Marco Arcelli told Semafor. Abroad, the company is eyeing China as its “next big hub,” with major projects and approvals already in motion, Arcelli said. The company already operates 300 megawatts there, with several gigawatts waiting to be greenlit, and aims to invest $30 billion in China by 2030. Chinese policies — including mandated offtake and subsidies for capital expenditure — help reduce risk and drive quicker investment decisions, Arcelli said, arguing that unless Europe, Japan, and South Korea adopt similar regulations, China could dominate the global hydrogen market by 2030, as it has with solar and batteries. —Manal Albarakati |

|

New EnergyFossil FuelsFinanceTechPolitics & Policy Emmanuel Croset/AFP via Getty Images Emmanuel Croset/AFP via Getty ImagesEVsPersonnelMedia |

|

|