|

Trapped in the hell of social comparison

A hypothesis about why Americans are unhappy with their economy.

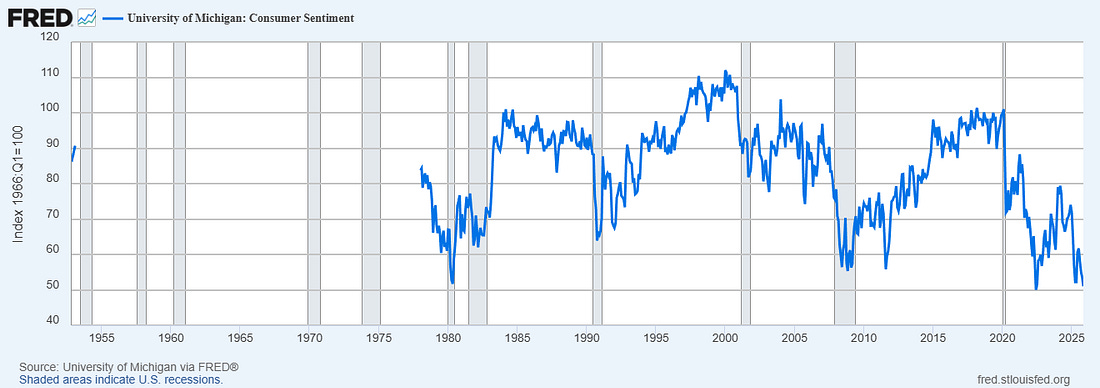

Interest rates have begun to come down. Inflation has mostly subsided, and the real economy is still doing decently well despite Trump’s tariffs. So why are American consumers more pessimistic than they were during the depths of the Great Recession or the inflation of the late 1970s?

It’s possible to spin all sorts of ad hoc hypotheses about why consumer sentiment has diverged from its traditional determinants. Perhaps Americans are upset about social issues and politics, and expressing this as dissatisfaction about the economy. Perhaps they’re mad that Trump seems to be trying to hurt the economy. Perhaps they’re scared that AI will take their jobs. And so on.

Here’s another hypothesis: Maybe Americans are down in the dumps because their perception of the “good life” is being warped by TikTok and Instagram.

I’ve been reading for many years about how social media would make Americans unhappier by prompting them to engage in more frequent social comparisons. In the 2010s, as happiness plummeted among young people, the standard story was that Facebook and Instagram were shoving our friends’ happiest moments in our faces — their smiling babies, their beautiful weddings, their exciting vacations — and instilling a sense of envy and inadequacy.

In fact, plenty of careful research found that using Facebook and Instagram made people at least temporarily unhappier, and there’s some evidence that social comparisons were the reason. Here’s Appel et al. (2016), reviewing the literature up to that point:

Cross-sectional evidence demonstrates a positive correlation between the amount of Facebook use and the frequency of social comparisons on Facebook…A similar pattern emerges for the impression of being inferior…Some of these studies…have documented an association between social comparison or envy and negative affective outcomes…

Causal relationships between Facebook use, social comparison, envy, and depression have also been established experimentally. For example, in a study about women's body image…women instructed to spend ten minutes looking at their Facebook page rated their mood lower than those looking at control websites. Furthermore, participants in the Facebook condition who had a strong tendency to compare their attractiveness to others were less satisfied with their physical appearance…

In summary, available evidence is largely consistent with the notion that Facebook use encourages unfavorable social comparisons and envy, which may in turn lead to depressed mood.

Note that during the 2010s, consumer confidence was high. Even if people were comparing their babies and vacations and boyfriends, this was not yet causing them to seethe with dissatisfaction over their material lifestyles. But social media today is very different than social media in the 2010s. It’s a lot more like television — young people nowadays spend very little time viewing content posted by their friends. Instead, they’re watching an algorithmic feed of strangers.

A lot of those strangers are “influencers” — people who either make a living or gain fame and popularity by posting about their lifestyles. And while some of those lifestyles might be humble and hardscrabble, in general they tend to be rich and leisurely.

When I asked a social media-obsessed Millennial I know to give me an example of a rich influencer, she immediately mentioned Rebecca Ma, better known by her online nickname Becca Bloom. Here’s Becca’s spectacular wedding:

And here’s a video of her and her husband letting Microsoft Copilot decide where to fly their private jet:

Most of Becca’s Instagram account is pictures of her taking trips to gorgeous, scenic locations and showing off fancy clothes and other possessions. Another example I heard was Alix Earle, whose posts mix dance performances with exotic vacations.

To be very clear, I am not criticizing, decrying, or denouncing social media influencers like this. Becca Bloom looks like a nice person that I might go to a party with — and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with having a beautiful wedding, hanging out on the beach, or visiting cities in Europe. But how many Americans can afford to live that lifestyle? Becca Bloom comes from a super-rich Hong Kong family, a successful entrepreneur who sold her technology company in 2018. She’s top 0.01% for sure.

There were rich people like that in 1920, or 1960, or 1990. But you almost never saw them. Maybe you co