| | In this edition, how tech companies are reasoning the risk-to-reward in their ambitious AI agendas, ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ |

| |  | Technology |  |

| |

|

- Anthropic vs. DoD intensifies

- Anti-ICE activists use tech

- Waymo faces injury

- Why ROI is obsolete

- The wrong apocalypse

How tech companies weigh risk to reward in the ambitious AI age, and an AI model that could help preserve coral reefs. |

|

Every tech company right now is being judged on the delicate dance between industry transformation and business preservation. This week we got a better read on how CEOs are weighing risk against long-term ambition. Take Microsoft. For the first time ever, it posted a $50 billion quarter in cloud revenue, up $10 billion from a decade ago. But that growth wasn’t good enough for Wall Street, and yesterday’s stock drop wiped out $357 billion in value, its steepest fall since 2020. Sure, there are jitters about an AI bubble. But the real worry is that Microsoft isn’t moving fast enough to blow up its own core services — namely, Office 365 — and turn them into some kind of magical AI experience (remember Bing chat?). If Microsoft cedes its grip on the corporate world, it becomes a data center and cloud services provider with thinner margins and a shallower moat. And then there’s Meta, which said it would double AI infrastructure spend to $135 billion. You’d expect investors to freak out a little in the absence of a straightforward plan to make money on all that compute, but shareholders rewarded Meta with a 10% stock pop. The most extreme version of managing through this paradox of change is Tesla. On Wednesday, Elon Musk said the company was ditching its iconic Model X and Model S cars to clear factory space for humanoid robots. He also said the company would funnel $2 billion from Tesla’s balance sheet over to xAI. Musk recognizes that making cars is a crappy business in the AI era, especially when China is willing to subsidize them and flood the market with cheap alternatives. It’s the on-board software that turns cars into revenue-generating robots that represents the value. And once you realize you’re a robotics company, it really makes no sense to waste time — or precious factory space — on a business that may soon be obsolete. As Microsoft and Meta try to ride the AI wave while carefully managing how their core businesses transition, Musk is already living in the future — and letting shareholders know they can either jump on board or see themselves out. There’s no risk-free option. Tesla’s stock dropped after the news, reflecting the risk in that strategy. Humanoid robots and autonomous cars could end up taking significantly longer than Musk hopes, and the company is facing stiffer competition than, say, Tesla and SpaceX did when they were getting started. But the slow and steady approach taken by other tech companies will only work for so long. |

|

Anthropic’s defense contract at risk |

| |  | Reed Albergotti |

| |

Denis Balibouse/Reuters Denis Balibouse/ReutersThe scuffle between Anthropic and the Defense Department over how Anthropic’s technology is used, which we first reported two weeks ago, has reignited in the media, putting a $200 million contract at greater risk. Anthropic’s dispute with the DoD centers on how, exactly, its technology should be used in lethal conflicts — a debate that could burn the startup’s relationship with the current government overall. It’s a topic we’ve been covering since last spring, when Anthropic took aim at President Donald Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act that initially drafted a moratorium on states from passing AI regulation (it was removed before the bill passed). Anthropic co-founder and CEO Dario Amodei added fuel to the fire in a blog post earlier this week, warning about the dire consequences of AI development. Anthropic’s critics — both in Washington and Silicon Valley — believe all this talk amounts to a disingenuous, self-interested attempt at passing AI regulations that will ultimately help incumbents like Anthropic. But all the evidence I’ve seen suggests Amodei is genuinely concerned about the effects of his inventions. And this is a story as old as time. Powerful technology always comes with risk, and inventors often struggle with the futility of trying to guard against misuse. Even if Anthropic were playing a cynical game of regulatory capture, the current playbook wouldn’t make much sense. Amodei would be better off joining other tech execs in playing nice with the Trump administration while trying to steer lawmakers subtly toward its goals. Instead, it’s in danger of ending up on the outside looking in. That might serve it down the road, but it isn’t doing itself any favors in the short term. |

|

How ICE protesters are using technology |

Evelyn Hockstein/Reuters Evelyn Hockstein/ReutersThe clash between immigration enforcement agents and protesters in Minneapolis is the latest front in a high-stakes global arms race between governments and their domestic foes over who has better technology — and who has the right to use it. Trump’s immigration crackdown — and the extra funding that came along with it — spearheaded an era of surveillance tech aided by Palantir and other powerful AI companies: Facial recognition apps that reveal a person’s immigration status, phone tracking technology, AI agents, and spyware that remotely hacks into phones and helps federal law enforcement target individuals. Activists are also tapping tech to try and fight back, Semafor’s Rachyl Jones reports. To warn community members when ICE agents are nearby, Sherman Austin, an activist and technician in Long Beach, California, created a national database of license plates connected with immigration operations, and a text alert system to track and broadcast the movements of federal agents. “They’re running around en masse. They won’t identify themselves,” Austin said. “This is a tool that we can at least use to keep track of their whereabouts, so we can tell our friends and neighbors when they’re nearby.” |

|

Waymo’s first reported human accident |

Brendan McDermid/Reuters Brendan McDermid/ReutersIt happened. Waymo hit a kid. It wasn’t fatal — minor injuries were reported — but it foreshadows the response of when one of Google’s vehicles will inevitably cause harm to a human. Last Friday in Santa Monica, California, a child ran into the road, directly ahead of the vehicle, which slowed down from 17 miles per hour to under 6 before making contact, according to the company. The same day, Waymo notified the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which indicated it will open an investigation into the incident. Waymo wrote a blog post on Wednesday, the first time news of the incident reached the broader public. That’s not an inherently offensive timeline, but it calls back to when regulators found discrepancies in General Motors’ reporting of an accident with a Cruise autonomous vehicle, which ended up contributing to GM’s decision to shutter the project. In a statement shared with Semafor, a Waymo spokesperson highlighted transparency as core to Waymo’s “safety-led culture.” “On the same day we voluntarily disclosed this incident to NHTSA, we prepared a statement and shared the details with a local journalist to ensure the information was available for public reporting,” she said. “We remain committed to proactive, voluntary disclosure as a pillar of building public trust and improving road safety.” To be sure, Waymos are significantly safer, statistically speaking, than human drivers. According to an analysis by the company, a human in the same scenario would have still hit the child, while going faster — 14 miles per hour. Whether Waymo can convince regulators and the public that few human accidents become an acceptable trade-off, is still being determined. |

|

On this week’s Mixed Signals, Bell Media CEO Sean Cohan joins Ben and Max to unpack the success of Heated Rivalry and how the gay Canadian hockey romance became an overnight cultural sensation amid Hollywood’s heralded vibe shift, as major production companies in the US have increasingly catered to broader or more conservative tastes. Cohan also talks about Bell’s strategy of using licensing deals to reach new audiences, the enduring power of a well-told romance, and why Canadian storytelling is only getting started on the global stage. |

|

Getting the most AI bang for your buck |

Scale AI CEO Jason Droege (right) and Semafor’s Reed Albergotti. Firebird Films/Semafor. Scale AI CEO Jason Droege (right) and Semafor’s Reed Albergotti. Firebird Films/Semafor.When people ask questions like “are companies getting ROI from their AI implementations,” they’re stuck in an old conversation — it’s not the right measurement. Companies know they can’t fall behind on automation, regardless of whether they can measure the impact. The question now is: What does it take to implement AI successfully? Is it plug and play? Does it require custom models or more fine-tuning after it’s created? “There’s probably — I’m just going to pick a number — 3,000 to 5,000 people in the world, frankly, who can implement critical workflows that deliver value,” Scale AI CEO Jason Droege said at a recent Semafor event. Scale, of course, employs a good handful of them, he said. Droege said the best of them have done work post-training AI models and have developed a sense for the strengths and weaknesses of specific models. Scale sends those employees directly into companies to understand the specific needs of customers, and then build systems tailored to their security and business needs. If that sounds reminiscent of Palantir’s “forward deployed engineer,” you wouldn’t be too far off base. In fact, Scale is now competing for Defense Department contracts, Palantir’s original feeding ground. But there’s no easy way of making AI work. It might be simple for software developers to just use AI, but not for companies with complex business processes. Watch the full interview with Droege here. |

|

End-of-world AI fears have one plausibility |

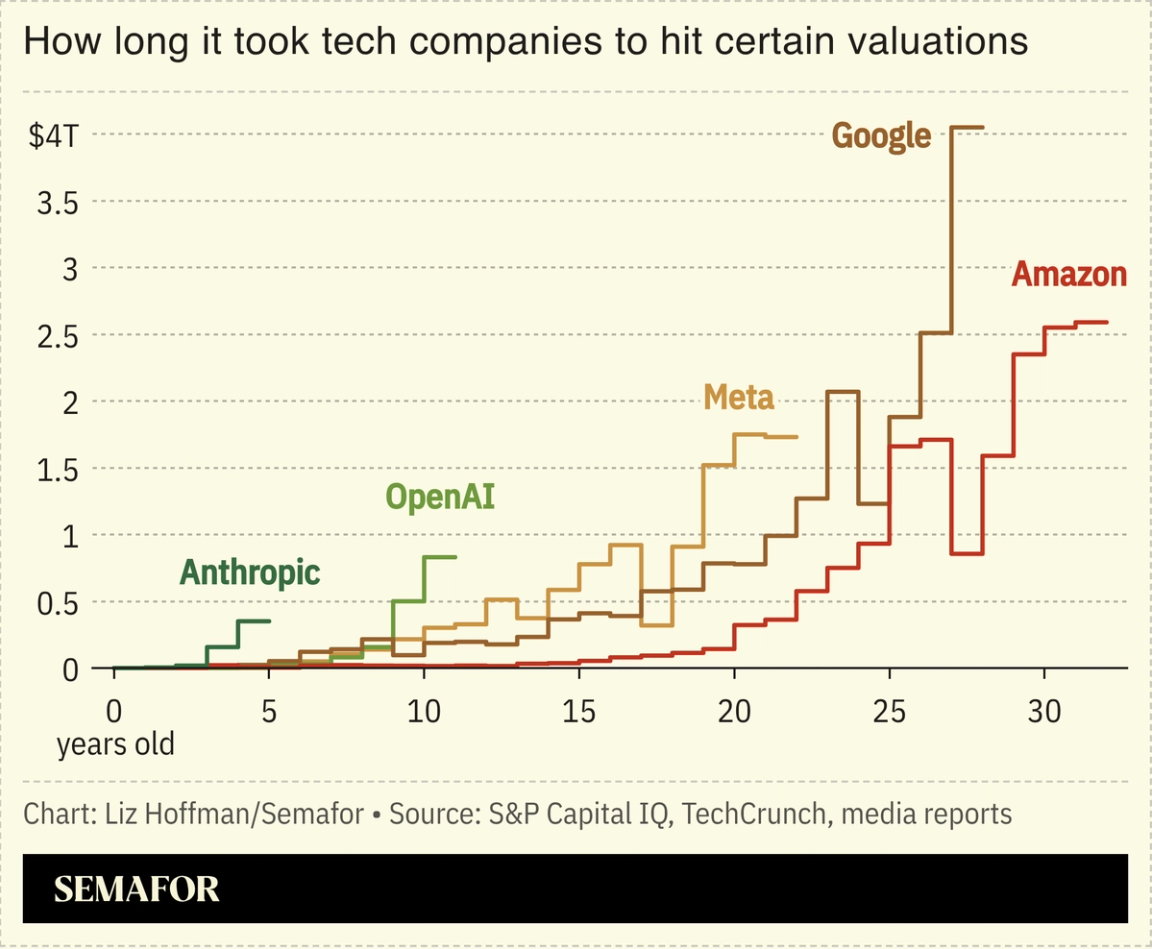

Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei’s essay this week warns about AI’s dystopian dangers — biological weapons, supercharged dictatorships, mass brainwashing. Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev read it and responded: You’re worried about the wrong apocalypse. Tenev points to the “staggering scale of wealth accruing to a select few in Silicon Valley, and how dangerous that can be,” writes Semafor’s Liz Hoffman. “‘AI becomes sentient and society collapses’ and ‘the masses take up pitchforks against the elite and society collapses’ get you to the same place. Amodei is worried about one risk, Tenev is raising the other.” At barely five years old, Anthropic is as valuable as Google was at 15 and Amazon at 22, long after those companies went public. And most of Google’s current $4 trillion valuation happened in the hands of public stockholders. “For future public shareholders of OpenAI or Anthropic to capture Google-sized gains, they would need to reach valuations in the tens or hundreds of trillions of dollars,” Liz writes. “Barring a collapse in AI valuations or a seismic redistribution of wealth like the proposed tax currently freaking out California billionaires, the gap may already be too big to close.” |

|

|