|

|

Why Trump’s Attack on Refugees Could Hurt Grandma

It’s immigrants from ‘shithole’ countries who care of our elderly, and nobody’s lining up to take their place.

Miami, Florida

MARYSE, 56, HAS BEEN A HOME CARE WORKER in the United States ever since she moved here from Haiti sixteen years ago. Over the years, she estimates, she’s cared for more than two dozen people. Most have been seniors in physical or cognitive decline—among them, a Purple Heart recipient who had served in the Army and a former pilot who had flown missions over France and Africa during World War II. She has also cared for younger people with physical disabilities, including one who had cerebral palsy and another who had suffered severe head trauma in a car accident.¹

It was not the career Maryse once imagined for herself, she told me last week. Back in Haiti, she was a journalist. But that was before a 2010 earthquake killed an estimated quarter million people and destroyed more than half of Haiti’s infrastructure, plunging the island nation into a state of extreme deprivation and violent anarchy.

At the time of the quake, Maryse was staying with family in the United States, her two children in tow, wondering what kind of life waited for them back home—or if they could even survive there at all. That’s when the Obama administration granted Haitians “temporary protected status” (TPS), a designation that allows foreigners to stay and work in the United States legally when their home country has become dangerous because of natural disaster, armed violence, or other “extraordinary” circumstances.

Maryse’s priority at that point was providing for her kids, and her English wasn’t good enough for media work in the states. At her sister’s urging, she says, she enrolled in classes to become a certified nursing assistant, following a well-worn path for Haitian immigrants who knew the high demand for caregivers meant it would lead to reliable employment—and who frequently saw caring for others as a calling, not just a paycheck.

The work has never been easy or simple. A typical day will involve some combination of cooking and driving, bathing clients (home care workers typically don’t refer to them as “patients”) and helping them with the toilet. Sometimes the most important thing is to provide simple companionship, she told me, whether it’s on a walk in the park to hear old stories or in front of the television to watch Wheel of Fortune.

The job is almost never just eight hours a day. The challenges include dealing with the physical strain of lifting adult human bodies. But Maryse says she doesn’t have a problem with what you might imagine as the jobs’ more difficult aspects, like the ickier parts of bathroom duty or the emotional drain of getting to know people just as they are in the twilight of their lives. “I really like helping these people and it reminds me how vulnerable we all are,” she said. “I do it with as much heart as I can.”

But these days Maryse has been preoccupied with another subject: Donald Trump’s anti-immigration agenda, and what it would mean for people like her.

An order that Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem issued in November revoked TPS for the roughly 330,000 Haitians who have it. And while a federal judge blocked that order right before it was to take effect last Tuesday, the Trump administration says it plans to appeal. At least for the moment, the administration is also ignoring pleas from a coalition of pro-immigration advocacy groups and high-profile Democrats—along with the occasional swing-district or -state Republican—to relent.

Trump’s determination to get these Haitians out of the country is a subset of his larger project to rid the United States of refugees from what he calls “shithole countries.” The way he and the MAGA faithful tell it, the Haitians are a burden on American society and a threat to its culture—a “filthy, dirty, disgusting” group of people so depraved that, as he infamously said during the 2024 campaign, they were eating their neighbors’ dogs and cats.

But just as the pet-eating story was apocryphal, Trump’s portrayal of the Haitian community’s role in society is way off—especially in places like South Florida, where so many Haitians are providing support for some of the most desperately needy people in society. If the refugees lose their right to stay they won’t be the only ones to suffer.

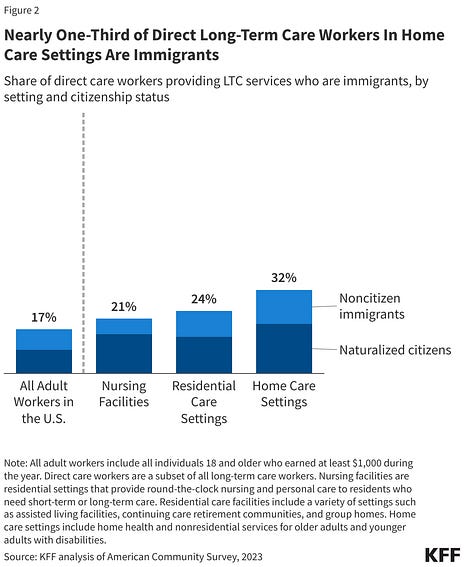

IT IS DIFFICULT TO IMAGINE what care for seniors and people with disabilities would even look like without a large immigrant component. While foreign-born citizens and noncitizens account for just 17 percent of the adult workforce, they make up 28 percent of the total direct care workforce, according to analyses by the policy research organizations KFF and PHI.²

This is not a case of immigrants taking jobs from Americans, most economists say. It’s a case of immigrants taking jobs Americans don’t want, because there are easier ways to make a living. “There are these other jobs—even fast food sometimes—where you can have more predictability and stable hours, and make similar money,” Rober