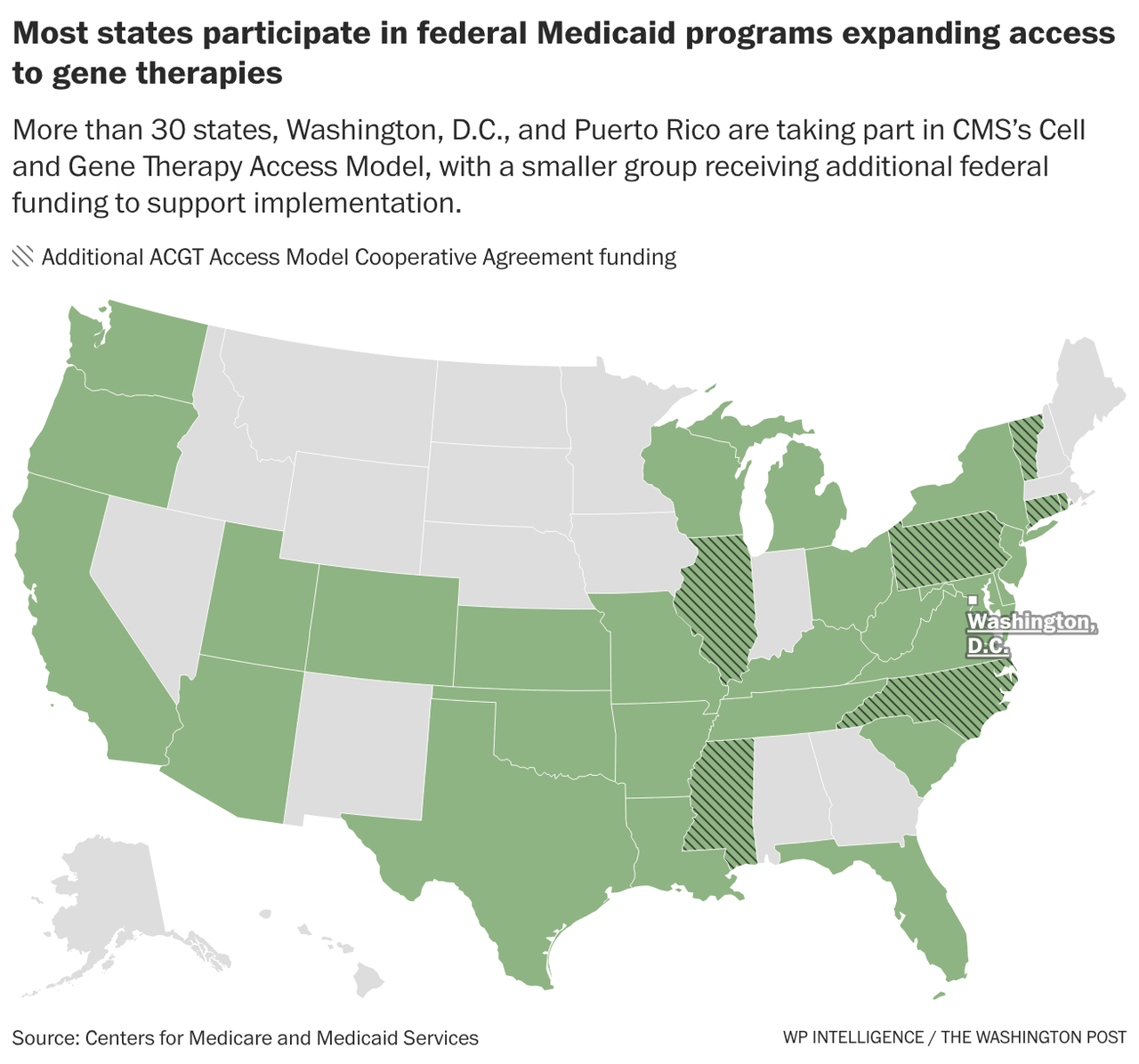

| |  | | | | |  | By Megan R. Wilson | Did someone forward this newsletter? Sign up here to get it in your inbox. In today’s issue: Our in-depth WP Intelligence report on Medicaid’s new approach to innovative yet pricey drugs. Botox shouldn’t be included in Medicare price talks, AbbVie claims in a new lawsuit. And lastly, four Democratic states are suing the Trump administration over public health grant cuts. It’s Thursday, and this is Health Brief. Do you have any story tips or health policy intel? Shoot me a note at megan.wilson@washpost.com. If you prefer to message me securely, I’m also on Signal at megan. 434. This newsletter is published by WP Intelligence, The Washington Post’s subscription service for professionals that provides business, policy and thought leaders with actionable insights. WP Intelligence operates independently from The Washington Post newsroom. Learn more about WP Intelligence. | | | |  | The Lead Brief | Washington tests a new way to bargain over high-cost cures: For the first time in Medicaid’s 60-year history, federal officials have negotiated prices for expensive treatments on behalf of states, allowing the government to get some money back if the therapies don’t work as anticipated, WP intelligence lead health care analyst Rebecca Adams writes. The program for sickle cell gene therapy treatments in some states started last year, with the final states launching last month. By the numbers: Thirty-two states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico are participating in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ voluntary program. Read the full report which we’re putting in front of the paywall for you. Why it matters: Cell and gene therapies offer medical breakthroughs, but barriers — including multimillion-dollar costs — prevent some consumers from benefiting. The therapies often offer patients a one-time round of treatment instead of a lifetime of care. The program is starting with sickle cell treatments, but other cell and gene therapies treat diseases such as cancer and certain rare diseases. The centralized role of the federal government in cutting these types of deals is new for Medicaid, the state and federal program for low-income Americans and people with disabilities. The political context: Remember how long Washington officials talked about whether to give Medicare the power to negotiate drug prices for older Americans? The federal government’s ability to use its market power was a key question when Medicare Part D, the federal government’s prescription drug benefit, was enacted in 2003. Congressional Republicans did not want the federal government to have so much bargaining leverage over the drug companies, instead seeking to have individual insurers handle negotiations. Medicare didn’t get that authority until former president Joe Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act into law in 2022. The Trump administration is taking a somewhat similar, yet more narrow, tact of using the federal government’s power on drug pricing that other Republican policymakers have long been averse to doing: testing out the negotiation approach in Medicaid through a pilot program. That means Congress doesn’t have to explicitly endorse it. |  | | Zoom in: The widespread interest from states demonstrates an eagerness to curb the high prices of treatments that are intended to help patients avoid hospitalization later. “It’s really difficult for states to implement these types of agreements on their own, not only operationally and from a contracting perspective, but also because they may not have the leverage individually,” said Rachel Sachs, a former Biden administration official and Washington University School of Law professor. But, the pioneering program is currently limited to treatments for sickle cell disease, a painful blood disorder that can cause severe pain and organ damage. And, so far, it’s only helping a fraction of people with sickle cell disease for several reasons: One of the treatments is not working as efficiently as first expected, not every patient meets the clinical criteria, treatment centers are limited, and the program is still in its early stages. What’s next: The project could serve as a template that could allow even more patients to receive life-changing but expensive treatments for other conditions. Federal officials are soliciting recommendations on expanding the model to other diseases, so patient groups and industry players have a window to help define the next steps. The move comes as the Food and Drug Administration is signaling more regulatory flexibility for cell and gene therapies. | | | |  | Industry Rx | The federal government improperly selected Botox for Medicare’s drug price negotiation program, according to a lawsuit filed by drugmaker AbbVie on Thursday. - The company’s lawsuit against the CMS and Department of Health and Human Services claims that Botox is a “plasma-derived product,” which AbbVie notes is a category of drugs exempted from negotiations under the Inflation Reduction Act.

- Last month, CMS selected Botox as one of the 15 drugs set to undergo price negotiation this year.

- Botox’s label notes that the product — used to treat wrinkles, chronic migraines and overactive bladder — contains “albumin, a derivative of human blood.” (Medicare does not cover Botox for cosmetic purposes.)

- Subjecting Botox to negotiation, AbbVie claims it violates the company’s constitutional rights by forcing it to offer the product at “confiscatory prices” and subjecting the company to a “one-sided price-setting process.” The suit alleges that the government is also violating AbbVie’s free speech rights by calling the negotiated price “fair” and implying the company agrees with the term. (Following the Medicare negotiation process, new prices are referred to as the “maximum fair price.”)

In its legal filing, AbbVie said that it wrote to, and met with, CMS officials “on several occasions” — and explained the Inflation Reduction Act’s provision that excluded products derived from human plasma from Medicare negotiation. The agency “never refuted AbbVie’s view,” the company said in its complaint. “And despite these multiple letters and meetings, CMS provided no feedback with respect to the application of the plasma-derived exclusion.” CMS said the agency does not comment on ongoing litigation. → AbbVie recently hired Checkmate Government Relations, a firm with ties to the Trump administration, to lobby on “life sciences related matters.” AbbVie and Checkmate Government Relations did not respond to a request for comment about the work the firm will be doing for the company. | | | |  | Litigation Report | Four Democratic-led states are suing the Trump administration over the cancellation of $600 million in public health grants, accusing the federal government of “using the tool of federal funding for partisan political purposes.” → On Wednesday, Illinois, California, Minnesota and Colorado filed the suit, which focuses on an effort last month by the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) directing agencies to slash funding in “disfavored states,” according to the suit. Earlier this week, HHS moved forward with notifying Congress about the cuts. President Donald Trump is “using federal funding to compel states and jurisdictions to follow his agenda,” said California Attorney General Rob Bonta in a statement. “Those efforts have all previously failed, and we expect that to happen once again.” Why it matters: The largest portion of the cuts, according to the lawsuit, hit a grant program aimed at bolstering public health infrastructure at state and local levels, including hiring more workers and modernizing their technology and data systems. Some of the other cuts would hit grants intended to help fund testing and treatment for HIV. The “grants are being terminated because they do not reflect agency priorities,” a spokesperson for HHS told my colleague Lena H. Sun in The Washington Post newsroom. - NEW: Lena has also learned about an additional 42 health grants that are targeted to be axed, according to sources who said notices were sent to congressional appropriators Wednesday. Her sources were granted anonymity to discuss the process. Experts say it's unclear how much money has already been spent, and how much is left.

In the legal filing focused on the initial cuts, the states argue they “will be unable to replace the lost federal dollars with their own money, especially because the cuts are immediate, made without warning or time to plan, and in the middle of funding cycles.” The states are asking a federal court to halt the funding cut and declare the OMB’s “targeting directive” — and any implications for funding stemming from it — unlawful. In a statement regarding the cuts, the Big Cities Health Coalition noted that Congress had previously approved the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention funding that is being rescinded. | | | | | | | | | | | | |